When draconian acts and abusive control of law combined, a disaster for the people is spelled. The Rocket re-looks at the history of the repealed Internal Security Act, and discovers that its far-reaching consequences are still alive today.

Remembering the Terror

It was October 27, 1987. Malaysia came under a wave of instability. The political boat was, once again, rocking, and irresponsible allegations of the possibility for ‘another May 13’ to happen resonated in the public sphere.

It was October 27, 1987. Malaysia came under a wave of instability. The political boat was, once again, rocking, and irresponsible allegations of the possibility for ‘another May 13’ to happen resonated in the public sphere.

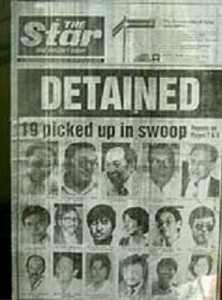

Overnight, 107 people were detained under the Internal Security Act, on the basis of maintaining public security. The notorious Operasi Lalang abused the ISA on the vague excuse of “public safety”.

The government, under Prime Minister Dr Mahathir Mohamad, went on a spree of ‘weeding’ operations across the country, throwing into custody a reckless number of persons comprising mostly opposition politicians and civil society leaders.

For the government of the day, it was deemed a necessary prevention to maintain security. For the people, it was a confusing mockery towards democracy.

That was 25 years ago. As we mark the 25th anniversary of this historical disgrace in human rights, we continue to fight against political oppression and seek freedom for all Malaysians.

Malicious Show of Power

The Internal Security Act 1960 is a preventive detention law in force in Malaysia. It was birthed during Malaya’s tougher days of fighting the heightened communist insurgency. ISA was perceived to be relevant at the time to curb ‘terrorist activities’ and ‘subversive elements’ detrimental to the nation’s stability.

For 52 years, it was used by the government of the day against not only politicians, but also against environmentalists, trade unionists, social activists and religious extremists, among others.

Tunku Abdul Rahman once defended the act’s necessity, promising that it will only be used for those threatening public order, never to be used against regular civilians or political opponents. The then Home Minister Tun Dr Ismail dismissed accusations of ISA as being ‘undemocratic’, justifying that its usage within the country’s context was, indeed, to ensure the ongoing process of democracy.

It was criticized then as it is now, but beyond the Emergency, the place of ISA in a maturing Malaysian society has started to become more and more questionable – especially when it is abused to serve ulterior needs.

Famous ISA detainees

In the October 1987 Ops Lalang, Lim Guan Eng was detained under the ISA for 18 months. Other detainees in this fell swoop included DAP’s Karpal Singh, PAS’ Khalid Samar, Aliran’s Chandra Muzaffar, Independent MP Ibrahim Ali, and Suaram’s Kua Kia Soong.

Dr Syed Husin Ali, a sociologist in the University of Malaya, was detained for almost six years (1974-1980) “for being involved willingly and knowingly in an attempt to overthrow the government by force and for cooperating with the communists.”

In 1991, Dr Jeffrey Kitingan, brother of the then Chief Minister of Sabah, was detained for two years “for trying to champion the secession of Sabah from the Federation of Malaysia”.

More recently, two Hindraf members and lawyers, V Ganabatirau, and R Kenghadharan were detained for two and a half years, together with DAP State Assemblyman M. Manoharan, who was elected while in detention.

Double ISA detainees include PAS politician Mohamad Sabu, DAP Parliamentary Leader Lim Kit Siang and PKR de facto leader Anwar Ibrahim.

Old wine in a new bottle – ISA rebranding

Carrying the burden of its notorious past, the hesitant Najib Razak found himself pressured between the cries of reform, and the grunts to hold on to laws and institutions that ensure the continuity of power.

Carrying the burden of its notorious past, the hesitant Najib Razak found himself pressured between the cries of reform, and the grunts to hold on to laws and institutions that ensure the continuity of power.

On the eve of Malaysia Day last year, anticipation greeted Najib’s purported ‘big’ speech. At the end of the night, Malaysians were offered a wave of promises by Najib’s administration to bring forth changes the country’s way of being managed.

This included the announcement to repeal the Banishment Act, the Emergency Ordinance as well as lifting three Emergency Proclamation in the country, and the decision to repeal the ISA.

But this didn’t spell the removal of the ISA and its essence altogether. After seven months, the draconian ISA was ‘replaced’ by a new, equally repressive law. In April 2012, a new Bill was tabled, taking the name of Security Offences (Special Measures) Act 2012, or SOSMA.

SOSMA is painted to have a much gentler nature, as compared to its old cousin, the ISA. The motive of its initiation remains similar: “to address security issues.”

But when NGOs, civil society organizations, activists, and legal experts took a closer look at SOSMA, they realized that while the new law marked some improvements in some areas, it was actually more repressive in others.

Once again, it seems that the Malaysian government is demonstrating yet another play of ‘bait and switch’ with human rights.

What’s wrong with SOSMA?

The bill has also been criticized as tightening restrictions or banning outright activities already under constraint, adding limits to previously unrestricted activities, and broadening police apprehension and surveillance powers in merely ‘rebranded’ ways.

The Bar Council has criticized SOSMA, saying that ‘security offences’ under the act are defined so widely as to be ambiguous.

Some of these offences include: actions to cause a substantial number of citizens to fear, organised violence against persons or property; to excite disaffection against the Yang di-Pertuan Agong; or which is prejudicial to public order or the security.

This wide ambit allows an almost limitless number of people to be detained for flimsy reasons under vague clauses.

The Bar Council recommended that the Act should use the definition found in the UN International Convention for the Suppression of the Financing of Terrorism 1999. It limits the definition of terrorist acts to those “intended to cause death or serious bodily injury” to civilians in order to intimidate a population or compel a government to do or abstain from certain action.

Another concern raised on SOSMA is that a suspect who has been acquitted may continue to be detained indefinitely while the prosecution exhausts all avenues of appeal.

“Now, all that is needed to be done is for the public prosecutor to (apply) to the court for the individual (to) be rearrested…what is the difference from the ISA?” questioned Pakatan Rakyat de facto leader Datuk Seri Anwar Ibrahim.

Under SOSMA, initial police detention is cut to a maximum of 28 days, after which the attorney-general must decide whether to prosecute and on what charges. This is an improvement from the ISA.

On the down side, judicial oversight is notably absent during the first 24 hours of police custody and such absence can be extended to the entire 28-day investigatory period.

Detainees who are released can be attached with an “electronic monitoring device” on their person.

There’s More…

Besides the new SOSMA, a barrage of three other legal amendments were pushed through to cement the government’s powers, some say the result is even worse than before!

Simultaneous amendments were tabled to the Penal Code, Evidence Act and Criminal Procedure Code.

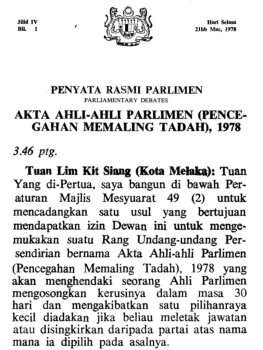

The new section 124B of the Penal Code is of particular concern as it introduces a new offence known as “Activity detrimental to parliamentary democracy”.

What exactly is that? Nobody know! The definition is so sketchy and yet it carries a high maximum sentence of 15 years jail.

It is disturbing to note the definition of “sensitive information” under the new Section 130A (i) is broad enough to encompass any document, information, or material, whether or not it is classified as “Top Secret”, “Secret”, “Confidential”, or “Restricted” by the state.

Public confidence in the government is shaken when oppressive laws are repealed with much fanfare, only to be replaced with equally -if not more abhorrent legislation that offends the spirit of legal reform.

Najib’s quadruple barrage of ticking time bombs is a rude awakening to voters that the BN government has no intention of real change. The only solution to end the desecration of peace-loving Malaysian’s fundamental liberties is to change the government. -The Rocket