By Pauline Wong

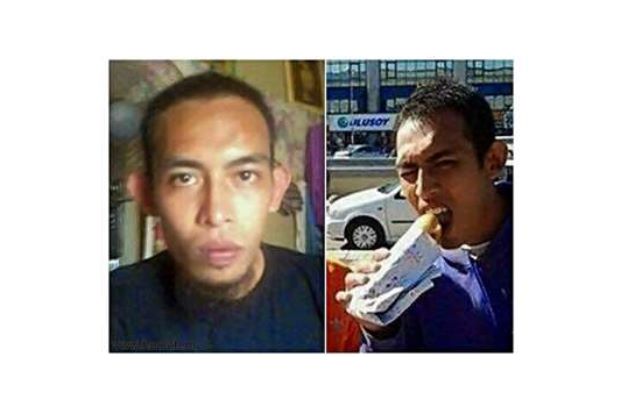

Two years ago, 26-year-old Ahmad Tarmimi Maliki became Malaysia’s first suicide bomber. The factory worker is responsible for the death of 25 elite Iraqi soldiers after he drove a military vehicle filled with explosives into the SWAT headquarters in Al-Anbar in May 2013.

The bombing preceded an attack on the headquarters by Islamic State of Iraq and Sham (ISIS) commandos.

The young man, described by his family as ‘quiet’, was working at a factory in Selangor since 2012, but he left in March 2013 to further his studies in the Middle East. From Facebook postings, it is learnt that Ahmad Tarmimi first went to Syria, through Turkey before going to Iraq, where he committed an act of terrorism.

Reports quoted his family members saying that he did not act strangely prior to his suicide, only that he became more pious and secretive.

Today, we remember him as the guy who has the dubious honour of being the first Malaysian to be a suicide bomber.

The question now is: Could our government, or police intelligence for that matter, have detected Ahmad Tarmimi’s deadly intentions and stopped him? Could a law, like the Prevention of Terrorism Act (POTA), have stopped him?

The POTA will be heard for the second time in Parliament today, and what it is supposed to do fight the increasingly worrying threat of terrorism by any means necessary. It is meant to prevent the likes of Ahmad Tarmimi, and to give the police the clout it needs to prevent, say, the 75 people it says it detained today for suspected involvement in the IS.

However, the POTA has not gone down well with many quarters.

The Malaysian Bar in a statement last week said the POTA is a “repressive law that is an affront to the rule of law and repugnant to the principles of natural justice”, and said that it was a shameless revival of laws like the draconian Internal Security Act 1960 (ISA).

“The Malaysian Bar remains steadfastly opposed to detention without trial. As such, we view the POTA as a backward step,” said Bar Council president Steven Thiru.

“Lack of transparency in detention without trial undermines public trust in law enforcement and reduces cooperation with authorities.

“Detention without trial also frustrates criminal investigations, by encouraging police to make an arrest before they have sufficient evidence to maintain a successful prosecution in open court,” he said.

The same criticisms were levelled years ago against the ISA, which disallowed judicial reviews of the indefinite detention without trial. The main contention with the ISA was also its arbitrary use to silence political dissent, and against political opponents.

While the POTA specifically defines that it is not to be used solely for political prosecution, there is little faith that this clause will be upheld.

Former Umno supreme council member Saifuddin Abdullah, who now heads the Global Movement of Moderates Foundation, was quoted by newsportal The Malaysian Insider as saying POTA will fail, as it would not address the root cause of terrorism.

Similarly, the United States’ own Patriot Act did not prevent the rise of the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (Isis), Saifuddin told the news portal.

“The Sedition Act and the ISA were frequently misused. In an atmosphere where the police are excessively using the Sedition Act and there are unjustified arrests, implementation of POTA starts with a trust deficit.”

Saifuddin was referring to the slew of arrests over the past few months against activists, opposition politicians and journalists under the Sedition Act — 158 people in total.

He said, “When the authorities introduced POTA with the heightened number of people (charged) under the Sedition Act, how can you expect people to simply accept your intention to propose POTA?”

His opinion seems to resonate with a recent statement by Bukit Aman counter-terrorism inspector Wan Ruzailan Wan Mat Rusoff, who was quoted by Malay daily Berita Harian as saying that some Malaysians join IS to cleanse themselves off sin.

“Some Muslim militants believe that their sexual sins would be forgiven and they will go to heaven if they die in the battlefield. They think that the huge sins they have committed will be gone when they fight in Syria,” he said.

Would POTA actually help stop them from doing this ‘sin cleansing’, and at what cost?

Already Malaysia is ranked lowly on human rights indexes across the world. Various international bodies like the Human Rights Council’s (HRC) Universal Periodic Review (UPR) have urged Malaysia to step up its defense of basic human rights of equality and put an end to discrimination.

United Nations member countries have also urged Malaysia to abolish capital punishment, repeal oppressive laws, and respect the rights of Orang Asli and individual religious practices — all of which, if the incidences of late are any indication, have been thoroughly ignored by the government.

And, truth be told — international standing is one thing, but the rights of Malaysia’s own citizens are paramount. Surely there are more holistic and less draconian ways to counter terrorism and quash the IS threat in Malaysia? Surely a greater understanding of religion, or better religious education, would be more effective to counter this in the long term? What guarantee is there that POTA would not be abused for political gain?

POTA is nothing more than a heavy-handed antibiotic to a disease. It does nothing to address the root causes of terrorism but prefers instead to address its outward symptoms. Like much of what the government does in addressing its problems — from the Goods and Services Tax to the Sedition Act — there is always a failure to cure the disease, instead, it is about playing catch-up to the symptoms of the disease.

– The Rocket