By Ralvin Manikam

They often seem like mere numbers in news reports — 10,000 protestors here, 5,000 protestors there. For every street rally, they are shown as nameless faces on television. Yet behind the veil, their actions have consequences — free speech has become a crime equivalent to theft or murder in this country. We tell the story of how ordinary people have had to face the harsh regime in their pursuit for change, and to make their voices heard.

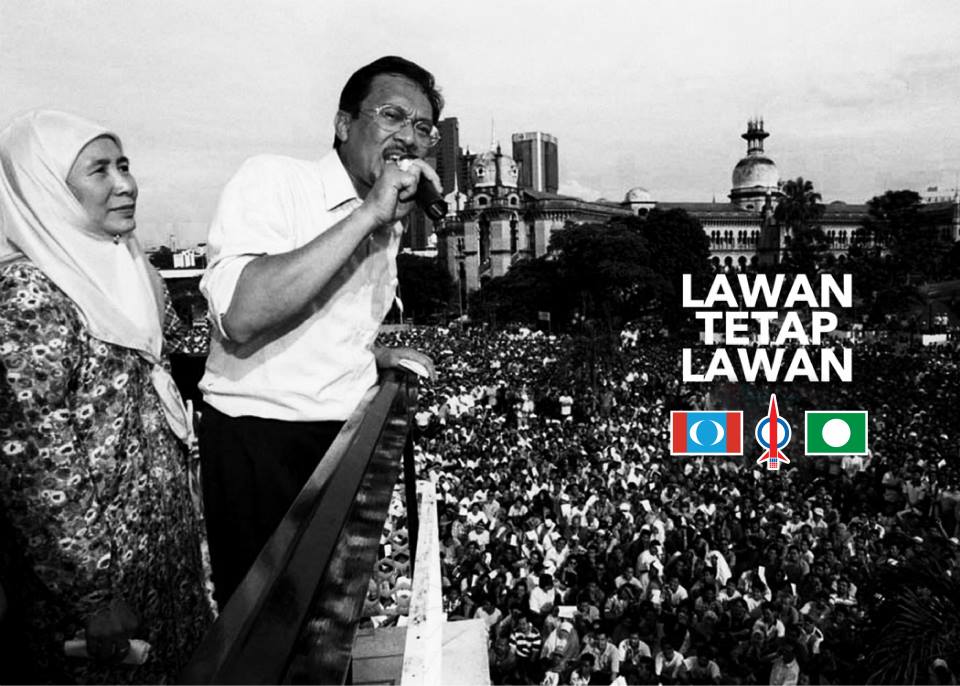

The year 1998 was a crucial year in Malaysian politics.

The year 1998 was a crucial year in Malaysian politics.

The towering Deputy Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim had fallen from his pedestal, on whims of the then-Prime Minister, Mahathir Mohamad, but little did the latter know that criminalising his protege for alleged sodomy and abuse of power would give birth to the Reformasi movement.

As a result, Malaysian politics was not the same again, it would see citizens of the country take to the streets to protest against the ruling regime. Unprecedented numbers of women and men walked hand in hand that their voices of dissent may be heard by all.

Yet almost nothing is known of the lives of those who take on the authorities in peaceful assemblies, sacrificing time that could otherwise be spent leisurely, without risking arrests.

Amongst those out there under the scorching sun, their fists in the air hailing “Reformasi! Reformasi! Reformasi!” even when up against a wall of men in helmets wielding batons and shields, are those making up the tour de force – the demonstrators themselves.

However, the consequences of being a free citizen is not one often shown in the media.

The Rocket had the opportunity to speak with a family, who, since 1998, have dedicated their lives to what they see as a fight for the future of the country – something they see as necessary, so that their children may look forward to a brighter Malaysia.

Nashita Md Nor and Bad Latiff, parents of four, come from families who are staunch Barisan Nasional supporters — something which they have decided to defy.

Being identified as the black sheep is not easy, Nashita told us in a recent interview. The couple and their kids, who attend pro-Pakatan protests, say they are shunned by certain family members who have opposite political leanings.

However, defiant as they are, protesting is something they insist is necessary to affect change in the country, because they want to be heard.

While other families spend time together at shopping malls or at the movies, Nashita and her family brave the blazing heat, believing that it would make a difference.

“We feel like we need to show the powers-that-be how angry we are about the state of things including the government’s tyranny,” Nashita said.

She recalled the Kesas Highway protest back in November 2000, when she was seven months pregnant. Her husband was in the organising committee of the protest, which was held on Nov 5, 2000, and was a PKR-sponsored rally in support of Anwar Ibrahim.

Nashitah had insisted on attending the protest, despite advise from others not to go.

“I feel like it was one of the most successful demonstrations staged, because many had showed up, it should be marked as a historical date,” she said.

She said if she chose not to go due to her pregnancy, it would be a loss for her, she would have missed out on experiencing the “kebangkitan rakyat” (rise of the people).

“I am one of those who believe that taking to the streets would impact decisions (by the government). For example, during the price hike of goods in 2007, when there was a constant hike in fuel prices, we had demonstrated every week; in IOI Mall, USJ KLCC, Gombak Cheras, and due to this, fuel prices and toll prices did not increase,” she said.

Bersih 3.0

However, there were times when her pursuit for a greater cause have worried her.

Bersih 3.0, was the height of police aggression, according to her. It was the single protest that made her doubt her decision to bring her children to protests, feeling it was dangerous.

“I did not want to bring my children to demo’s anymore,” she said.

The Bersih 3.0 rally on April 28, 2012, was a sit-in protest organised by the Coalition for Clean and Fair Elections (Bersih) in Dataran Merdeka, Kuala Lumpur. The rally was to demand for a clean and fair elections. Over 80,000 protestors had filled the streets of KL, making it the largest protest in Malaysian history. It started out peacefully but turned ugly when police fired tear gas at the crowd, who they said had broken through the barriers which were put up around Dataran Merdeka.

“It was like a stampede, if any one of us tripped and fell, we would have died,” Nashita said, recalling the chaos.

In what she described as a “war zone”, her daughter Asiah, according to her, had “lost her mind”, running around out of control when the water canons and tear gasses were fired.

“I believe that a protest is successful when police react aggressively, threatening the safety of the protestors,” she said, adding that this is a common belief amongst seasoned protestors.

Thing have changed since then, authorities are much more sanguine now when dealing with protestors more peacefully than they were back then.

“You even have protests in stadiums, where things don’t get out of control,” she said, recalling Black 505 after GE 13.

Locked up

Physical danger is one thing for Nashita, but getting arrested and detained is far more serious.

Of the four times she had been arrested, three were spent in lock-up.

Back then, detained protestors would insist on not changing into lock-up attire, the purple robe that is of common sight nowadays. The police would concur, she said.

“The latest arrest was different,” she said, referring to the Anti-GST protest at the Kelana Jaya Customs Department on March 23. This latest arrest saw harsher police treatment.

“It was almost as if they (the police) were intent on making us feel inferior. The warden was very strict.”

All detainees were forced to don the lock-up attire like crooks and thieves.

“Being in the lock-up , you’d wonder if the people are speaking up for you, you’d hope that you’re not forgotten, I’m sure that my husband in jail right now, feels the same way.”

Her husband has about nine months ahead of him, struggling in jail for the offence of holding a protest during the Perak constitutional crisis.

Her husband, who is known as Abang Bad, was one of the protestors who had blocked the road on the way to the Perak State Assembly, protesting the swearing-in of incoming Mentri Besar Zambry Abdul Kadir during the Perak constitutional crisis in 2009.

Along with 12 others, the protestors were sentenced to 10 months in jail for their involvement.

Pakatan supporters such as themselves were outraged at BN’s power grab of the state following defection from four PR representatives. Claiming to be independent, three of them vouched their support for Barisan Nasional along with Bota assemblyperson Datuk Nasarudin Hashim who rejoined UMNO, reversing the majority in the state assembly back into BN hands after PR rightfully gained control of it in the 2008 general elections.

It was deemed a coup de tat, and it had spurred protests outside the State Assembly Hall. Protestors had refused to endorse the new MB, elected through undemocratic means, and the ‘Perak 13’ are spending 10 months in jail that began April this year for their actions.

Free speech is a crime

It is this side of ‘protesting’ that people do not see. The right to free speech, in this country, comes with heavy consequences.

Nashitah said that her children found it hard to hold in their tears when meeting him in prison.

“People always say that if we fight, as we do, we could one day be locked up, even the possibility of losing our job – but these are just spoken words, nothing would prepare you for when it really happens.”

Bad, who is a mechanical engineer by profession, was involved in projects such as the construction of the Kuala Lumpur Twin Towers (KLCC); he was even posted in Abu Dhabi, Chicago and Melbourne for work.

“My husband is someone who can contribute to society, and does not deserve to be behind bars. He is not a criminal; not a convict.”

Visiting him in jail isn’t easy, according to Nashitah, the family could hardly see his face through the thick glass.

Asiah, who is their eldest daughter, misses her father, misses how he embraces her in the morning when she wakes up.

“Now that my father is not here with us, it just feels… empty,” Aishah says. “But he tells me to keep up the struggle, fight on and don’t give up.”

It is true: their names do not carry the same weight or demand the same public respect if compared to the big names, such as Anwar Ibrahim, Rafizi Ramli, or other politicians. They are not greeted with “YB” (Yang Berhormat) or “Datuk Seri” by the common Malaysian.

But this does not mean they are any less important, nor that they are not changing our nation in any way they can. They are the ones who had taken to the streets instead of silently standing by, and in this, perhaps is their greatest strength: that ordinary people can still make their voices heard, no matter the consequences that come.

– The Rocket