By Pauline Wong

The recently passed amendments to the Sedition Act and the newly-minted Prevention of Terrorism Act have been divisive, to say the least. Opinions on these two Acts have been completely on opposite ends, with on side saying it is necessary to protect public peace and order, and the other end saying it does exactly the opposite. Which side is right? In the light of the increasingly racist, homophobic and misogynic environment — largely perpetuated by politicians themselves — is it better to have laws to prevent that? On the other hand, what price do we pay for this so-called ‘prevention’? We lay it out, and then, dear reader, you can decide for yourself if you should be afraid of the Big, Bad, Sedition Act.

As children, we were told that if we did bad things, the police would come and take us away to lock-up. Our parents told us the men in blue would come and catch us if we didn’t do our chores, if we played truant from school, or if we misbehaved.

Those were but childish scares, used by our parents to frighten us into good behaviour. However, the understanding was always: if we did bad things, we would be punished.

Today, it is harder to tell what those bad things are.

The recently-passed amendments to the Sedition Act 1948 suddenly changes what ‘bad things’ mean. It prescribed punishments for certain deeds, but what is so wrong about those deeds?

Before this, we knew for sure that bad things were things like robbery, theft, murder, or abuse. If we beat somebody, it was bad. If we cheated somebody, that was bad too. Worse still if we hurt someone so badly that he dies.

Bad things today, however, include speaking your mind on your personal Facebook page, criticising your government, or expressing that you don’t agree with certain religious authorities.

In the amendments to the Sedition Act, even if you so much as ‘shared’ a post which someone finds ‘bad’, you will be punished and the policeman will take you to jail.

There are no safeguards, no clear-cut definitions of what’s wrong and right, and it places all the power to judge in the hands of a select few.

In punishing everything, the Sedition Act has blurred the lines between good and bad.

What exactly are these amendments?

For starters, the key amendments include:

>> Removal of judicial discretion in sentencing:

What it is: When a charge of sedition is brought to Court, the Court cannot choose to impose fines upon conviction, instead it is a compulsory imprisonment of three years. Previously, a sedition offence would, on conviction of first offence, be liable to a fine of not exceeding RM5,000 or to imprisonment for a term not exceeding three years or to both, and, for a subsequent offence, to imprisonment for a term not exceeding five years.

What this means: A 17-year-old, for example, who innocently shares a post which is deemed seditious (cause to be published) can be liable to a 3-year sentence. Lawyer Syahredzan Johan in an article on newsportal Malay Mail Online said that there is absolutely no justification for this.

“For an Act as wide as the Sedition Act, where no element of intention must be proven, as well as the disproportionately high conviction rate, judicial discretion in sentencing may at least cushion some of the more draconian aspects of the law. It may be difficult for the Court to acquit a person as the Act casts a wide net on what is deemed to be seditious, but at the very least the Court has options when it comes to sentencing. The bill will take away that option,” he said.

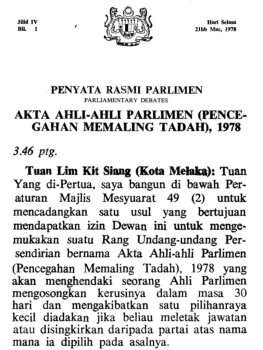

“Also, Members of Parliament beware! A conviction for under the Sedition will result in an MP losing his or her seat,” he added.

>> Restriction of travel:

What it is: If an application is made by the Public Prosecutor (DPP), the Court shall order the person charged with sedition to surrender his travel documents, thus preventing him from leaving the country.

What this means: The word ‘shall’, says Syahredzan, suggest that the Court has no discretion on restricting travel if an application is made. While the Courts have power to order a person on bail to surrender their travel documents, the discretion should be the Courts’, and the DPP has to justify the need to impose such restrictions. With this amendment, the Court has to order the accused to give up their passports, and such, even before the person is found guilty.

So a person who faces charges of sedition will have his basic right to mobility and free movement restricted. This goes against Article 5 and 9 of the Federal Constitution which guarantees the rights of all citizens to the freedom of movement and liberty.

>> No bail for any aggravated offence which causes bodily injury or damage to property.

What this is: The proposed Section 4(1A) provides for a new offence — an aggravated offence where the seditious act ‘causes bodily injury or damage to property’. The sentence upon conviction is a minimum of 5 years imprisonment and maximum 20 years imprisonment.

What this means: If you attend a protest which is deemed to have incited hatred or hostility against a group of persons based on race, or religion, and accidentally break a flower pot belonging to the Kuala Lumpur City Hall, you could end up in the slammer.

Syahredzan said there is no need for this new ‘offence’.

“Why the need for a new offence? The Penal Code has offences to deal with those who make statements conducing to public mischief or to provoke a breach of the peace. Why not deal with such acts through the Penal Code?

“What is more inexplicable is the provision to deny bail for an accused charged under this new proposed Section 4(1A). Again, the Court has no discretion. Once a certificate is given by the DPP, no bail shall be granted for the person. There is absolutely no reason why bail should not be granted for a Section 4(1A) offence.

“The underlying principle of bail is to secure attendance of the accused, not to punish the accused. If it is really not in the public interest for accused person to be released on bail, the Prosecution should submit the justifications to deny bail to the Court. It should then be left to the Courts to determine whether bail should be granted or not.

>> Bill now inserts seditious tendency of promoting feelings of ill-will hostility or hatred between persons or groups on grounds of religion.

What this is: Exactly what it says on the tin. However, this mirrors the existing sections of the Penal Code, where it penalises the offences of uttering words with deliberate intent to wound the religious feelings of any person and causing disharmony, disunity, enmity, hatred or ill will on grounds of religion.

“The crucial difference is that unlike the Penal Code offences, the element of intention need not be proven, as long as it can be shown that there is the requisite seditious tendency,” says Syahredzan.

What this means: There is no burden of proof. There is no need to prove that those words were indeed intended to incite hostility or hate, that someone has deliberately decided to strew chaos or hate.

>> Special order to ‘block’ websites that publish seditious material whose owner/origin cannot be determined

What it is: The Court shall, upon the prosecution making an application to the satisfaction of the Sessions Court, order the Malaysian Communications and Multimedia Commission (MCMC) to block access to a site. The content of this site, if deemed to incite hatred and the continuation of which could cause injury or harm, is to be blocked.

What this means: Anonymous comments deemed seditious shall lead to the website containing said seditious comments being blocked. This could mean anything from a unidentified blog to even Facebook.

Unlike the correct course of justice where an accused is innocent until proven guilty, the amendments and the Act itself presumes guilt before innocence, and treats the accused as if he were already guilty by denying bail and restricting movement.

The fact is, the Sedition Act is not about ‘protecting’ people from the perils of ‘free speech’. The Sedition Act is repulsive because it makes a mockery of what is wrong and right, and it ignores the rule of law.

The amendments make it so that there are no safeguards and no judiciary discretion to this inherently flawed law. Without safeguards, the course of justice is perverted and mutilated beyond recognition.

Suddenly, expressing yourself becomes ‘bad’ and ‘wrong’, the same as if you were to rob a house or steal someone’s bag.

If the lines between whats wrong or right becomes blurred, who’s to say that the very act to prevent lawlessness, would not increase it?

By restricting free speech to the point where all thoughts and ideas become repressed, who is to say that those repressed would not seek more extreme, physical ways to express their feelings?

The danger in the Sedition Act amendments goes beyond just “be careful what you say on Facebook”.

It twists the whole notion of right and wrong on its head, makes a mockery of the law, and flies in the face of justice.

Read more: Worrying slide down human rights ladder

Read more: Bulldozed and dazed

– The Rocket