Article by Member of Parliament for Kluang, Wong Shu Qi on 21 January 2021:

The COVID-19 pandemic is like Grimm Brothers’ magic mirror that tells the truth about the real state of things in our country. It exposes the problems not only in our healthcare delivery system, but also in other areas of governance.

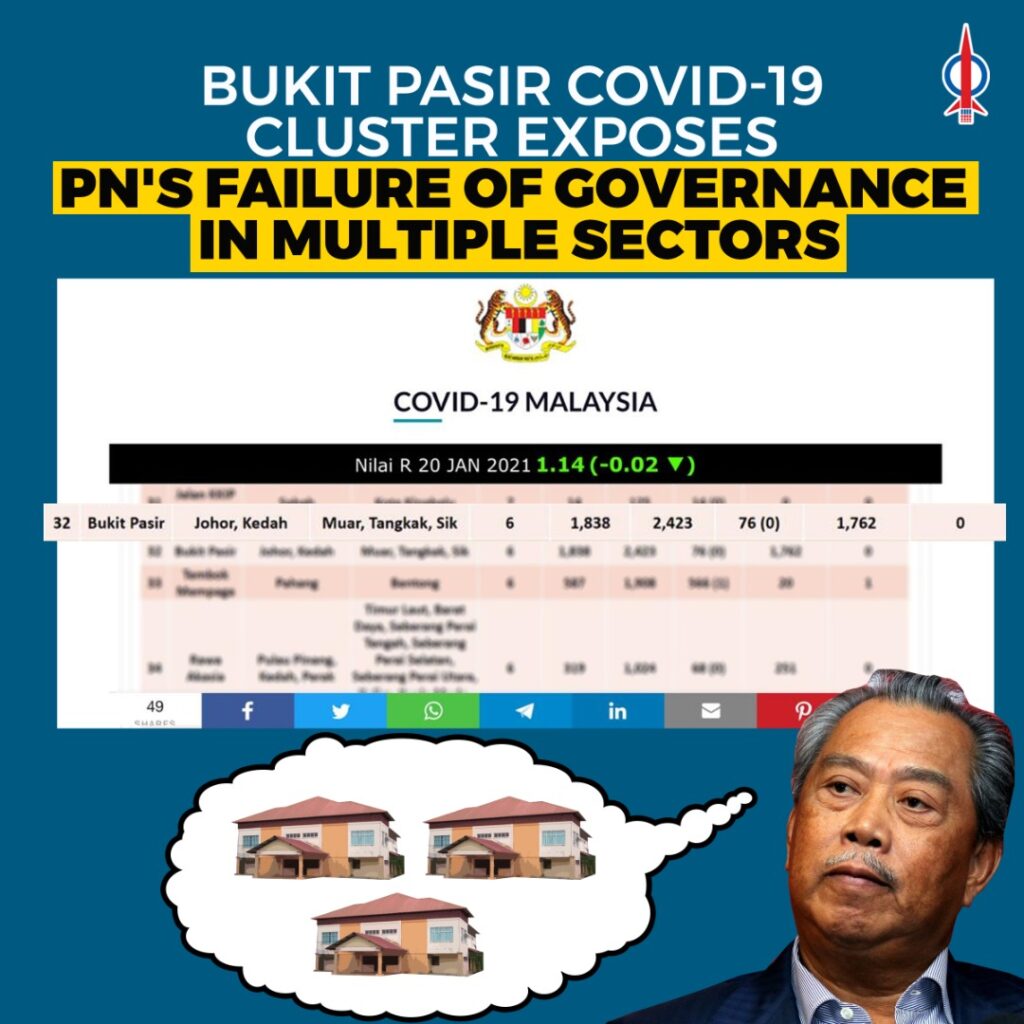

Recently, Prime Minister Tan Sri Muhyiddin Yassin was put on the defensive when reports of him spending RM35 million to build community halls in his constituency emerged on social media. In the midst of a health crisis, the Prime Minister, after his government’s massive failure to contain the pandemic, did not seem to understand the priority, the needs as well as the sentiments of ordinary Malaysians who are watching the rising number of COVID-19 cases daily, and experiencing the pandemic getting closer and closer to their own homes.

The Bukit Pasir cluster, located right at the heart of Pagoh, the Prime Minister’s constituency, has recorded 1,838 cases with one patient being treated in the intensive care unit (ICU). What Pagoh, and Malaysia for that matter, need at this moment is definitely not three community halls costing taxpayers RM35 million. We need money, resources and manpower invested heavily into fighting the pandemic, saving lives and protecting livelihood.

Yet, more than that, the Bukit Pasir cluster also revealed a more deep seated problem in our country: how our poor migrant worker policy had eventually triggered an infection outbreak in a small town in Johor.

Bukit Pasir, the furniture-making town

Bukit Pasir is a modest town in the district of Muar. Travelers coming from Kuala Lumpur to the historical Bandar Maharani, Muar – literally the Queen’s City – will have to first pass Bukit Pasir. The town is unassuming but for the pride of the area, and Muar in general, its furniture industry. Compared to the town’s century old long history, furniture-making is relatively new but the industry was so lucrative that a private Chinese Secondary School in the area actually offered woodwork vocational course back in the 80s and 90s to supply manpower to the industry. Students were recruited by furniture-making companies even before graduation. Unfortunately, due to high maintenance cost, the school ended the course after the 2002 cohort.

The furniture industry, however, thrives into the third decade of the 21st century. There are about 800 furniture factories in the district of Muar which includes Bukit Pasir. Overall, the concentration of the industry in this area contributed to more than half the furniture exports of Malaysia. The industry however is highly labour intensive. Yet today, there are fewer locals who are willing to work in a furniture factory perceived as 3D – dirty, dangerous and difficult. Manufacturers therefore have no choice but to rely on migrant workers.

The industry did try to automate to reduce dependency on low-skill human labour. A report released by the Academy of Sciences Malaysia in July 2018 observed that, about 60% of furniture companies employ some sort of automation in their production activities. On top of that, 78% of furniture manufacturers expressed willingness to invest in automation. They acknowledged the advantages of automation such as reduced operating cost, reduced number of workers, increased productivity and so on.

Unfortunately, 71.4% and 57.1% of the furniture manufacturers who participated in the survey stated that, high capital investment and high maintenance cost, respectively, are the barriers for them to automate further.

From shortage of labour to pandemic outbreak

When the Perikatan Nasional (PN) federal government announced the first COVID-19 lockdown in March 2020, the intake of migrant workers was stopped. Consequently, labour shortage became acute. The furniture industry faced a huge dilemma. On one hand, the worldwide demand for furniture experienced a surge with the proliferation of Working From Home (WFH). On the other hand, production cannot cope with incoming orders as factories faced shortage of workers. In the end, some of these factories had to “borrow” workers from Klang Valley. With the large movements of people from COVID-19 hotspots into Bukit Pasir, the next thing we know, there was a virus outbreak in this quiet, unassuming small town.

Last week alone, 106 migrant workers tested COVID-19 positive were transported from Bukit Pasir to Serdang to be quarantined. This confirmed that the workers were originally registered in Selangor and somehow ended up working in factories in Bukit Pasir.

This cluster exposed the inherent problem with our country’s handling of migrant workers.

There were only 160,892 migrant workers in red zones who undertook COVID-19 swab test from 1 December 2020 to 17 January 2021 as announced by the Prime Minister in his speech on 18 January this year. The number is minute compared to the 1.5 million documented migrant workers and perhaps, an equal number of undocumented migrant workers in the country today.

Undocumented migrant workers, especially those who are asymptomatic, will definitely avoid going to the authority to undergo COVID-19 test for fear of exposure and deportation. Even the documented ones may be hesitant to be tested at the risk of losing their jobs and livelihood.

With millions of migrant workers going underground and not willing to come forward for voluntary COVID-19 tests, and yet are continually employed in labour-starved industries, we will face the same issue over and over again even when vaccination starts in Malaysia.

Pandemic management is not just health management

The Bukit Pasir cluster demonstrates to us that at least for Malaysia, COVID-19 is more than just a health crisis. It exposes a crisis of governance in all sorts of sectors.

Many have called for a thorough long-term reform in our migrant workers management and it goes without saying that such reform is utterly important, but there are currently much more pressing and expedient measures to be taken in this time of crisis:

Firstly, the government should make a decision to swab all migrant workers regardless of their legal status. In fact, COVID-19 test, at employers’ expense, should be made compulsory for the migrant workers rehiring programme aimed at legalisation of undocumented workers.

Secondly, PN should continue Pakatan Harapan’s Malaysia@Work policy to encourage employment of locals including TVET trainees. The policy was introduced by the then Finance Minister Lim Guan Eng under Belanjawan 2020. Unfortunately, PN abandoned the policy after February 2020.

In fact, it is even more crucial now to encourage our youth affected by post-COVID-19 unemployment to pursue skill certifications under the various TVET schemes. I believe local manufacturers, such as the furniture factories in Bukit Pasir, will be more than happy to work with government TVET institutions if they can provide a stable supply of skilled labour to the industry.

Thirdly, we are not doing enough to help most of the furniture industry players to upgrade and move up the value chain. 86% of the furniture industry are SMEs. In 2019, the PH government announced a RM550 million allocation for both the manufacturing and service sectors to implement automation. The programme provides a matching grant of RM2 million for a manufacturer and RM50,000 for a service company who is investing in automation. However, immediately after the change of the government, the grant was reduced to a maximum of RM1 million for each manufacturer.

In reality, the Muar Furniture Association estimated that even the smaller factories in Muar have to spend RM1 to 2 million annually just for machine upgrades while the bigger players have to invest up to RM20 million a year. As of today, the local furniture industry is still relying on imported machineries which are not only expensive but also come with high maintenance price tags. If the government is going to ask them to do massive automation to reduce the dependency on human labour, we need to at least maintain the quantum of the matching grants provided under PH.

Even then, for serious players, government grants are too small compared to their capital investment. More importantly, local manufacturers must have access to cheaper credit with longer tenure. The entire support system must be built in order for Malaysia to remain competitive. In fact, in the long run, we need to nurture our own industrial automation sector capable of supplying not only to the local market but also a global one.

The pandemic is a crisis. But crises also present numerous opportunities; granted those who are in charge get their acts together. However, we have yet to see any paradigm shift in the government. For the migrant workers question, for example, there is still no policy solution in sight to help the industry to unlock their larger potential. This is frightening to say the least. In 2019, the Malaysian furniture industry’s export was worth a total of RM11.38 billion, and as we have seen, the sector is still expanding. Without any further intervention, the Bukit Pasir cluster is a time bomb waiting to explode again and again, and we are only here talking about one sector of the economy.