by Chung Hosanna

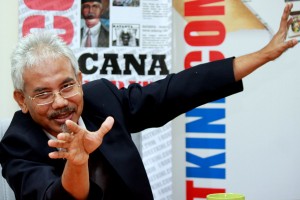

After 25 years of lecturing, Professor Dr Mohamad Tajuddin Mohamad Rasdi has come to the conclusion that our public universities have failed. The University Technology Malaysia (UTM) architecture lecturer passionately defends his views about the lost mission of universities.

“Our universities have totally failed to develop humanity. We can create people to work in offices, but we have failed to develop the larger potential of a person who can contribute to the community, the country and the world,” says the seasoned academician.

Tajuddin calls out the current ‘trade mindset’ prevailing in public universities which, he says, are churning out students like products.

Despite achieving 100% employment rate, these graduates go on to do the work of production workers and not ‘ideas people’. Their design, ideas and creativity skills are different from an overseas graduate.

“Not that ideas people are more important than production workers… but a production worker is at the level of diploma. If you want to just produce engineers and architects, you can have a technical school to train them by repetition,” he says.

The objective to emphasize on a student’s career instead of human development is reflected in the restrictive curriculum of public universities where 80% is devoted to course subjects and only 20% for human development. When career is over emphasised, the wholesome development of the Person is left out.

“Perhaps there’s a misunderstanding about our role to build a ‘world class university’ instead of a ‘civilised society’. We are in trouble if (the former) is what if we’re after,” Tajuddin says this is a handicap to the development of various disciplines.

Rankings cannot measure contribution

The Penang-born architect expresses surprise at the public furore over the drop in Malaysian universities place in international rankings. He points out that such rankings cannot correctly reflect whether the university is producing students that are able to contribute to society.

Public universities are heavily subsidised by the government and in that sense are less driven by the bottom line. Universities are either driven to contribute to society or for commercial interest- these are the only two choices. Hence, public universities should place contribution to society as its foremost goal.

“I would measure lecturers and students by their direct contribution to society. Where are your papers published? How many books have you written to educate the people?” Tajuddin has written many books, journal articles, and papers on cultural and value based design ideas in the realm of community architecture.

“It boggles my mind to think that we chase after rankings to attract foreigners to our university; when our primary duty is towards our local graduates. This is very strange. Do we want to serve the local community or attract the international community? It’s a case of robbing Peter to pay Paul.”

Tajuddin thinks Malaysian universities are ‘jumping the gun’ by trying to achieve international recognition without having first done its part to inspire and educate the local community.

If Ivy League universities are the benchmark, Tajuddin questions whether local universities would follow in Harvard’s footsteps to allow its lecturers to speak out freely in public about all issues under the sun.

Don’t listen to your Vice Chancellor

Many local lecturers are prohibited from expressing controversial or anti-establishment views, case in point being constitutional law expert Professor Aziz Bari of the International Islamic University who was suspended for expressing his views on a decree by the Sultan of Selangor on the 2011 JAIS church raid.

Saddened by Aziz Bari’s suspension, Tajuddin wrote an article about what he terms the ‘loss of academic license’ among Malaysian academia.

A profound silence of academician’s views exists in our local public space. In the case of the Lynas (Kuantan rare earth plant), none of the environmental professors had publicly expressed their expert views. Neither was there any response by knowledgeable academicians on the purported Anwar sex videos.

This absence is only partly attributed to the so-called culture of fear that has been instilled and reinforced over the years.

Quite apart from being deterred by the fear syndrome, Tajuddin says many academicians are unaware of their social responsibility to use the knowledge they have gained to educate the larger public. They think their job is only to teach students how to pass exams.

Quite apart from being deterred by the fear syndrome, Tajuddin says many academicians are unaware of their social responsibility to use the knowledge they have gained to educate the larger public. They think their job is only to teach students how to pass exams.

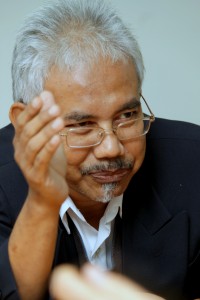

Tajuddin relates a story of how a friend once advised him to ‘play the game’ in order to be promoted. However, he refused, preferring to listen to his conscience. Eventually, Tajuddin was promoted ahead of his friend. “The next book I want to write is called ‘Don’t Listen to the Vice Chancellor’,” he quips.

According to the New Zealand Public University Audit Report, universities that restrict or fail to encourage its lecturers to engage in public discourse can lose their licenses. This is a far cry from the local KPI-centric administrators’ practice of stifling and prodding lecturers.

“Creativity is… letting them mess around”

Mollycoddled lecturers will in turn produce students who are timid intellectually as well as in life. Tajuddin warns that creativity cannot thrive in a restrictive environment.

While many universities claim to emphasise on creativity, they do not understand that the creative process involves a larger realisation of the meaning of life, says Tajuddin. Administrators and academics must know the importance of encouraging this.

“Let a student mess around, he will become creative. If you try to control him with a lot of donts, it wont work,” says Tajuddin, who was formerly the Director of KALAM (Center for the Study of Built Environment in the Malay World).

Although an expert on Islamic architecture, Tajuddin has spoken out against the ‘Malay-isation of Malaysian architecture’, he criticises the lack of balanced representation of other cultures in our national architecture.

He notes that in discussing this topic, many students dare not voice out their controversial views during classes, they choose to express their views about racism in architecture in their assignments.

“I asked the students in private, whether they were afraid of the Malay students (gangsters)? Being marked by the university as a radical? I think a certain culture of fear exists. I tell them that they are free to speak anything in my class, I can accept criticism… but they dare not.”

Students treated like ‘pariahs’

Many students who dare not speak out have low self esteem bred from the mentality of being treated disrespectfully, says Tajuddin.

He relates incidents where many support staff in universities treat students rudely, “like slaves and pariahs”. How can students rise up as the future generation of leaders if they are treated in this manner?

The 50-year-old lecturer also told The Rocket that the “militaristic stance” of the guards in universities and the presence of imposing gateways make the university seem like a boarding school.

He questioned the rationale of preventing outsiders from entering the university. Instead, he suggested that universities make available night classes for the community. A multi-functional university environment can unleash freedom of knowledge.

Tajuddin drew a comparison with Indonesian universities, which grant wide autonomy to its students. On the campus of Universitas Indonesia, students prepare lectures and have power to govern their own affairs. There is no such thing as Deputy Vice Chancellor for Student Affairs, or a Student Affairs Department.

As a result, students are directly responsible to the next generation of students. They run community programs, mini lectures for the (paying) public, and generate income through tuition for other students. With such strong student representation, even the government fears the students.

In contrast, Tajuddin says he has never seen strong student election spirit in local public universities. In UTM, the Faculty of the Built Environment even had to hold a lucky draw to encourage students to come out to vote!

Many students do not believe in the idea of student representation, because they have not met their student reps or seen them conduct activities in faculties. Tajuddin decries the lack of “mature political activity” among public university students.

Beyond 4.0 students

So what should we learn in our universities? What should be the foundation of our education system?

From our discussion with Tajuddin, he emphasizes on respect for fellow humans, love for all civilization, and a keen sense of awareness that knowledge permeates the great universe.

Economic concerns are not even close to being enough. We have to move beyond the ‘live to eat’ mindset of subsistence if we want to groom students who are entrepreneurial and creative.

Tajuddin tells us that a successful student is not just one with a 4.0 academic average. He attributes his success in architecture as being inspired by his understanding of Islam and relationship with life.

“This is what I advise parents who want their child to be a doctor, lawyer, accountant, high achiever. You don’t just want them to be an engineer… but someone who knows his responsibilities as a human… a good person.”

We couldn’t agree more. –The Rocket

Ed: We have since corrected a factual error regarding Dr Tajuddin’s position in KALAM. Thank you for pointing that out.

Correction: he was the director of KALAM. Someone else is the director of KALAM right now since 2008. Please check your information again.

Pingback: The Rocket — One Malay’s take on bible burning

prof tajuddin is the best in the university. i hope the best for him as my dear mentor and his dear wife. of course his international views can change these current situations to higher level.