Chief Minister of Penang and DAP Secretary General Lim Guan Eng was the first to be arrested during the infamous operation Lalang clampdown, and he was the last of the 1987 batch to be released. Here, he shares his experience under the draconian ISA

What are your thoughts on the ISA, which has now been in place for five decades?

What are your thoughts on the ISA, which has now been in place for five decades?

It is definitely a very draconian legislation. When you look at it theoretically, you don’t get the real gist of it until it actually happens. When one considers the oppression, suppression and repression which the ISA and other related laws encourage, it simply goes against basic human rights and human decency. If you look at the extent of the law itself, it becomes real when it happens to an actual person.

Firstly, you are denied your basic human rights, your dignity and humanity; love doesn’t exist in there. You are denied the basic love of your family, compassion and you become just a digit, no longer a person with a name and identity. In short, you are denied freedom.

We are all creatures created by God meant to roam around freely. We are born free and should die free. When laws impose limitations on our freedom and choices, life becomes unnatural.

Even if one were simply locked up in his bedroom without newspapers or some connection to the outside world, it is already stressful. Just imagine a detention cell where they don’t allow you to know the time of day as the lights are kept on 24/7 and the only human contact is your IO (investigating officer). It gets to the point where although it is perverse and you may have hated him in the beginning, you do look forward to seeing him because at least it breaks the monotony of the days.

By allowing one person absolute power to decide another human being’s future, I think we are going against nature. As they say, power corrupts, and absolute power corrupts absolutely. So this is where torture and abuse, whether mental or physical, happens. They will stop at nothing just to break you down so that you will toe the line. Again, this is unnatural because you are forcing somebody against their will.

Even though the physical imprisonment of ISA may not happen to all Malaysians, but we are all still victims because of the fear it creates. The greatest freedom is perhaps freedom from fear because otherwise, you are unable to fulfill your true potential.

This law encourages people to lie and punishes people who speak the truth. It also impedes the administration of real justice and democracy. As long as the ISA exists, opposition to injustice as dictated by all religions will not prevail. Look around the world at all developed countries; they are democracies because that is the way to success. The ISA is a stumbling block towards Malaysia’s progress.

Please tell us about the process of your arrest and detention.

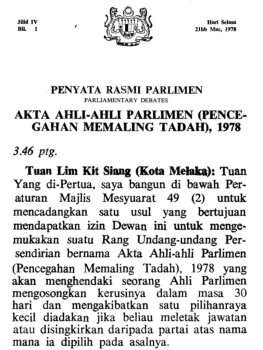

I had just been elected as a Member of Parliament for about ten months (after the 1986 general election) when the police summoned me to Jalan Bandar station in Kuala Lumpur. Upon recording the affidavit, I lodged a police report, criticising the government’s actions. After that, the officer asked me to sit and wait for another official. I waited but it took some time for him to come over. I had to rush back to Parliament as it was in session. So I said it was all right, and requested that the official call me again later. But the police refused to let me go. I began to wonder if something had gone wrong.

He told me to sit down and then showed me a document, saying, “You are thus informed you are now under the ISA detention order.” I could not believe it.

I asked him if there was any mistake. As a 26-year old, was I posing a threat to national security? But we knew there was certainly a hidden political agenda as there was a fierce political ruckus raging in UMNO. With all the internal fighting raging in their party, the leaders needed a scapegoat. I became the first detainee and the last ever to be released.

What were the conditions like in there?

During interrogations, it was a case of them refusing to believe my answers while I refused to cooperate with him. It was ridiculous because they even asked, “What is your name?” I replied that if they didn’t know who I was, they may have got the wrong person and should release me immediately.

They were failing miserably in their efforts to grill me and got fed up, hence they retaliated by putting me into a blue cell, a completely blue room. There was only a ventilator as the fan did not work. But it was a big fan with large blades, and in the middle of the fan was a hook. I asked them what the hook was for and they told me it was for hanging up those who were uncooperative. Thankfully I never found out if that was actually true! But they kept trying to intimidate me.

They stopped me from sleeping. I was seated on a wooden chair and light was casting on my face, just like in a movie. I still didn’t answer any of their questions. Instead I confronted them. I was young then, and hot-headed. I told them that whatever I said would not be correctly recorded anyway, so they might as well write down whatever they wanted.

The officer was getting so upset that I defied his orders, and he then refused to let me sleep for 48 hours. After being interrogated for 48 hours, I was completely exhausted. I tried to sleep but they were yelling at me. Afterwards I fell sick with a high fever. They were scared and sent me to the cell. So I stayed there for three days. They called a doctor to examine me and I was given some medicine.

When they questioned me again later, they were not so strict anymore, urging me to provide them with some information, saying it was their duty. Their attitude did become milder and it was good to be treated a bit gently. We knew the law, so they dared not do silly things. I refused to answer and stated “unwilling to answer” on their charge sheet. After it was finished, the report was sent to the Home Affairs Ministry.

There were five charges against me, including defending the rights of a primary Chinese School and criticising the inept teachers being sent to the school as well as censuring the MCA Cooperative Society’s syndicate, which was a big issue at that time. Due to the shenanigans going on in the cooperative, many people lost their hard-earned savings amounting to RM 1.4 billion. The fifth charge was because I had voiced my concerns about those living in poverty and held a demonstration. But these charges were clearly political witch-hunting because the police had not arrested or questioned us at the time of the incidents.

After 60 days in prison alone, you were sent to the Kamunting detention centre. What happened then?

I was detained, and my father rushed to the police station to see me, but they arrested him too. In short, they had lured him over, and it was a big blow to him. They hoped he would give up and surrender.

But then, after seeing this stubborn guy who was not giving up, they tried to upset him, asking me to appear on TV and write a confession letter to admit my “mistake” so I told him, “If I were an actor, I would have already had a career on TV. But I’m no Chow Yuen Fatt, so do not invite me on TV.” They wanted me to write a letter of confession, admit my mistake, and support Mahathir. I said to him, no need for me to support Mahathir, as he had so many supporters. Therefore, we were accused of being too contentious and sent to Kamunting.

Was life at the Kamunting centre more bearable?

Up to that point in my life, I had never experienced anything as trying as my imprisonment. I was struggling to endure the detention. You can experiment for yourself – lock yourself in a room, all day long with no escape. No newspaper, without your handset, leaving your phone outside. You have food and a place to sleep but…

You may not be able to bear it even for half a day. Imagine if you were in detention camp, not for half a day, or one whole day but days and weeks and months. In the beginning, we weren’t even given a mattress; we just slept on the cold cement floor. It affected my back after a while.

Once, I awoke in the middle of the night to find ants using my stomach as a bridge to carry a dead cockroach. But due to my back problems, it took me a while to be able to move, by which time the ants had already crossed over with their catch.

The food, of course, was terrible. The rice had small stones in it and the vegetables had sand. The meat given would be a small piece of fish or chicken and often it was just salted fish. Since my release, I avoid salted fish.

The cell itself was a small room with a toilet outside. It’s difficult without a built-in toilet, as you have to ask the police to open the door for you. You need to shout, and wait patiently for them. Sometimes they wouldn’t show up.

As for a bed, it is basically the concrete that you lay on. There was barely anything there, no newspaper or any information from outside. You’d dream about it. You read news from the old newspapers they used to wrap up your meals in. Initially we did that but they found us out soon enough.

So then we prayed hard that the newspapers would be a Chinese, English or Malay daily. But if there was a Tamil or a Jawi script paper, we couldn’t understand it and could only look at the pictures.

Discovering a Chinese, English or Malay daily was exciting and we would keep these papers. I read them over a hundred times, the same papers, I would read from left to right, upside down, reading it over and over, and would flip through again when I was bored.

When they found this out, they stopped wrapping the food in old papers, using plastic instead. Then life was boring as usual. In these times, we had to stare at the wall and watch mosquitoes or ants walking around.

Did you think about your date of release?

You might think of it initially, but you forget it as time passes. Thinking of it is like torturing yourself because there is no time limitation for the ISA. The detention order could be for 16 months or for 18 years. One person was in detention for over 18 years.

By reading books about Nelson Mandela detained for 26 years, you’d be so grateful! Console yourself that he was jailed for 26 years. By comparison, two years is minor!

My father and I were the last detainees freed. There were only two of us left inside that section. That site could house 600 prisoners, but there was only the two of us there, such a waste of public funds. We were both released last, on 19 April 1989. We were the first to be detained, and the last to be released. No doubt, this had to do with Mahathir’s personal feelings.

If you’re locked up, it’s not as difficult as your son being jailed, too. That must have been really torturous. So I salute my father for enduring this l. I knew very well that should I be released one day, I’d be even more motivated to fight as they had blatantly defied the law. They were casually violating laws, and I had to prove them wrong.

I was sure to come back, and struggle harder to fight them.

What was it like for your family to endure your detention period?

For a person, it depends on the strength of your convictions and commitments to the cause that led to your imprisonment. Are you really committed to the cause that led to the loss of your liberty? This is really tested at these moments. Either you emerge stronger or you come out broken, and it is, of course, hardest on the family.

Children, in particular, will not understand the situation so it is very difficult for them. But it can also help to strengthen family bonds after you endure such a traumatising experience. Of course, there are also families which end up breaking apart due to the detention so there are two sides to the coin.

It is hard for families to ever really share the experiences of what the detained person is going through. But if you have commitment and abiding faith that is unshaken, then you will emerge stronger than before and more determined to change the structures. It may seem like an impossible task but Malaysians should persevere in demanding the repeal of such laws.

In light of the 50th anniversary of the Act, what should and can Malaysians do about this law?

They should continue to oppose it and demand for its unconditional repeal through campaigns showing that this law is a stain on our common Malaysian identity. Whether we take an active approach such as becoming involved in politics or an inactive one such as being aware and voting, every Malaysian must stand up and be counted. We must oppose not just the ISA, but OSA (Official Secrets Act), the PPPA (Printing Presses and Publications Act) and the Sedition Act. -The Rocket