My name is Hayley Lee and I’m currently a 3rd Year student studying Environmental Sciences in the UK.

I’ve recently finished my 5-month internship under ADUN for Kampung Tunku and was privileged to join her in campaigning for one of the seats during the Sabah state elections back in late September 2020.

This has been my experience.

The Sabah Elections

“The drains in Sabah are like the drains in the Peninsular in the 90s”, is what one of the assistant councillors told me when we were doing house-to-house visits at one of the kampungs in Bingkor, Keningau.

I had been working in YB Lim Yi Wei’s office (state assembly woman for DUN Kampung Tunku in Petaling Jaya) for slightly over a month when she had first mentioned our office flying over to help campaign for one of the Warisan Party seats (in alliance with DAP) for the Sabah elections.

Fast forward a week and a half later, we were carrying 25kgs of campaign T-shirts each and hastily checking in to our 6:40am flight.

Once we were in Bingkor, following the agenda that day, we were en route to Mukim Bunga Raya when one of the campaigners, Joyce, asked “Have you seen this yet? I think you might want to take a photo of this”, while stopping her car at a junction. Written across a white banner in striking black paint; ADA ASPAL, ADA UNDI.

“Aspal”, better known as asphalt, refers to resurfaced roads. The banner was a form of protest to political parties, that the locals would only vote provided they were given basic infrastructure. In this case, roads.

In Peninsular, it costs approximately RM70,000 to resurface the distance of 2,500m2 of road excluding additional costs such as safety and preliminaries. In East Malaysia, where the majority of paths to kampungs are soil and gravel, the government plays a very important role.

This is because they hold the power to improve transportation, ultimately influencing the efficiency in children going to schools, farmers selling their livestock or agriculture, and access to other facilities such as hospitals – impacting the value of literacy rates and the state’s economy.

Unlike peninsular, much of the roads in Sabah were resurfaced in patches; approximately 2m2 of tar, followed by 2m2 more of gravel, and repeated.

This pattern continued for what felt like kilometres, trailing into Mukim Bunga Raya and a few other kampungs we had visited throughout the week we were there for. When we asked the locals about this ‘pattern’, their responses were simple.

Because certain kampungs had previously voted Barisan Nasional into power, and so only those who did would receive proper roads. These roads, paid using the constituency’s peruntukan, or allocated budget by the government, are completed by a contractor according to the height and distance of asphalt to be laid onto the land.

Why am I telling you about asphalt? Because I’m certain, no contractor in the world would conduct their work in patches, so where did the money for the untarred gravel roads go?

Up until my internship with YB Lim Yi Wei, I had never been to any political talks (ceramahs) or been active in politics before.

So, you can imagine the treat I was in for when YB Tony Pua spoke briefly about his experience on the 1MDB exposé and how it had come to justice, when the Warisan party members had told stories about them leaving their previous parties due to first hand corruption, and my personal favourite, when YB Tuan Lim Guan Eng spoke about the Prime Minister’s threat to these local communities of taking away their water or electricity if they hadn’t voted for him.

Being an environmental sciences student, I felt a very personal connection to YB Tuan Lim Guan Eng’s talk.

Through my university lectures, research and class discussions on an average person’s basic needs such as the management of water and electricity distribution on grids, the more I listened, the bigger the stump in my chest became. “Kenapa boleh ugut orang Sabah?”, YB Tuan Lim Guan Eng asked the crowd, roughly translating to “How can they threaten the Sabahan people?”

To think that the country’s leader, the Prime Minister, had threatened to deprive the many rural villages in one whole state by taking away their basic needs for survival with the limited resources they had, was essentially in my eyes, killing them completely.

This is the culture of bribery in Sabah because dirty politicians and crony capitalism who have abused its value for decades, are willing to pay virtually any amount of money or resource to ensure they are constantly kept in a position of power.

Imagine depriving the basic necessities of a farmer with a daily wage of RM66.60, then presenting almost 10 times that value to him all at once, for him to place a marker written ‘X’ next to ‘Perikatan Nasional’. These are real people, with families and livelihoods at stake, whom our government are toying with.

In these kampung areas, electricity is provided only to houses that are adjacent to the main road while those that aren’t, are required to pay to retrieve energy supply.

The lack of electricity is also reflected in Kota Kinabalu, Sabah’s capital, where populations continuously face water and electricity cuts throughout the day. In August of this year, The News Straits Times reported the federal government’s commitment to returning Sabah’s national utility company, Sabah Electricity Sdn. Bhd. (SESB), which generates, transmits and distributes electricity to the entire state.

These efforts were put to a halt when the Perikatan Nasional (PN) coalition put a hold on the plan. SESB’s ownership is divided between two parties: the Sabah state government (20%) and Tenaga Nasional Berhad (80%), a Peninsular-based electricity utility company, and according to their website, “the largest publicly-listed power company in Southeast Asia”.

The irony is that a company worth MYR 99.03 billion in assets and is a monopoly within its own industry, is unable to provide a single state electricity – something I’m certain would not be let off easily in Peninsular.

“Mantap Pertanian Mantap Bingkor”, roughly translating to ‘Strong Agriculture, Strong Bingkor’ – the slogan our N.40 Bingkor candidate campaigned with. Peter Saili, born in Keningau, was raised in a family of farmers. It is this background that has allowed him to inherit the practice into a career. In 2016, Peter joined politics in an aim to defend the rights of the rakyat (citizens) of Keningau. Although this was his second time contending, our team was confident that his efforts for Bingkor would be successful due to the initiatives he intended to launch as below:

- Champion agriculture by distributing 10,000 tree saplings to locals and to improve their farming techniques, with his personal experience, in order to ensure higher efficiency for larger yields.

- The second was infrastructure of roads to farms. Peter intended to start a Road Aid Fund to cover the cost of machinery and additional materials to better the journey of farmers to Tamus (morning markets).

- Women empowerment programmes, influenced by his seven sisters, to encourage local women to join economy development-based projects.

- The handing out of private land grants to farmers to improve soil cultivation and farming practices.

This information was plastered across all Peter’s campaign flyers because it was important to communicate to locals why the person who had their best interests was the best fit candidate for N.40 Bingkor.

On later days of the campaign trail, I was given the opportunity to follow Peter around and take photos for the visits he was making around Bingkor. At every house we went to at nearly 60 kampungs, Peter greeted every local with a big smile on his face and the warmest “Kopisanangan!” (Hello!). This included locals who supported opposition parties and those who sat in his opponents’ “markas” – a common method of campaigning in East Malaysia.

A “markas” refers to the headquarters of a respective political party who essentially sets up camp in a kampung to win favour of locals living there. To run even a single ‘“markas” is expensive because the party is required to pay for the scarce electricity supply in the area, cater for three meals a day, provide drinks such as alcohol, and blank forms of entertainment (e.g. karaoke) every day to ensure locals are constantly on their side during campaign season.

Using this strategy, it is also a way to hear about local gossip that could be brewing within your opponent’s party. At almost all 60 kampungs we visited, Perikatan Nasional had set up at least one “markas” in the area.

Coming to his late 60s, Peter’s stamina throughout the campaign trail was something I admired – mainly because even in my early 20s, I was exhausted myself. His usual days started at 6am at one of the Tamus (morning markets) in Bingkor, followed by house-to-house visits at a minimum of two to four kampungs – larger kampungs took longer hours due to the number of houses they contained, more events/ceramahs at 7pm, office meetings at 11pm and officially ending at 12am. In car rides, Peter would stay more and more quiet closer to Election Day, both fatigue and the rakyat’s choice coming to surface.

His opponent’s team were doing visits only on the day before elections. It was rumoured that locals were allegedly getting ‘handouts’ to ensure they would vote for the ‘correct’ party. Approximately a month after Election Day, MalaysiaKini publishes an article stating, “Bingkor rep denies vote-buying on Sabah polling day”. The article stated that Bersih’s election observers had documented a long queue of voters outside PN Robert Tawik’s office (https://www.malaysiakini.com/news/546556).

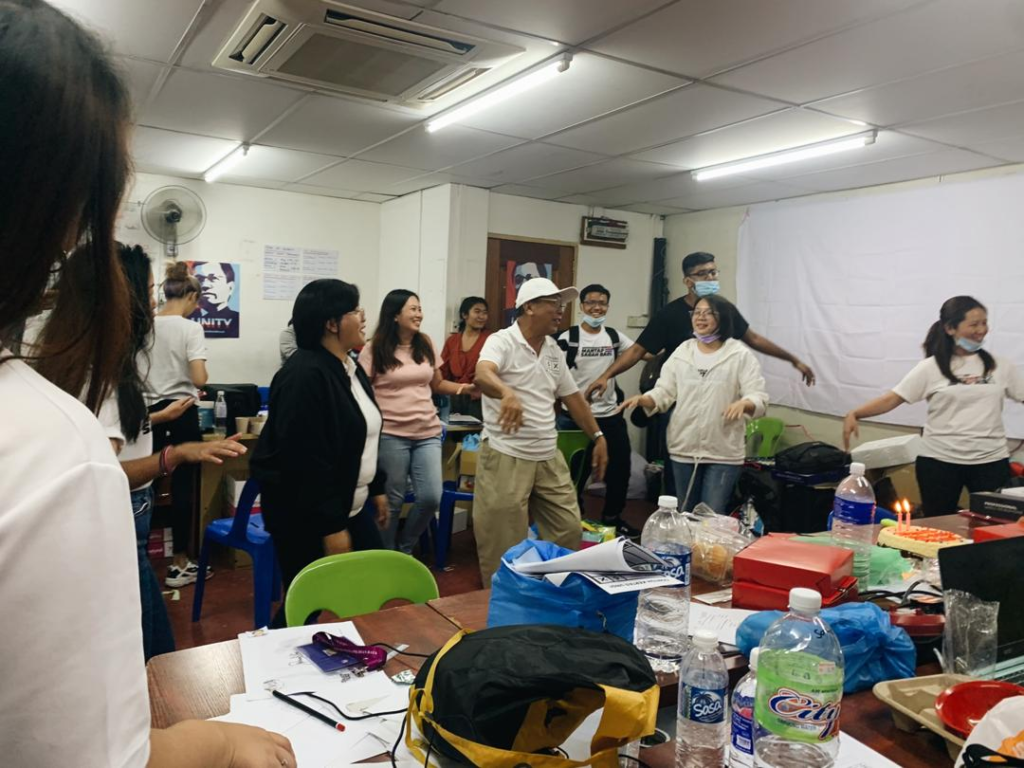

September 27th, as we came back to the office from our respective polling stations, we watched the votes rise and fall on the projected screen in the centre of the room. On the live broadcast, former Prime Minister Najib Razak celebrated with Barisan Nasional members, the alliance for the Perikatan Nasional party, in what looked like a fancy banquet room.

Peter had lost the seat to N.40 Bingkor. I don’t think I’ll ever forget the expression on Peter’s face that evening because although he was sporting his usual warm smile, you could see the defeat in his eyes. In a room of thirty teary-eyed people, Peter made his speech for his team when no one had the words to speak. Because that’s what Peter was – a leader who persistently showed guidance even in the most fragile of times.

In Keningau today, almost three months after the elections, headlines read “Aid for Keningau Hospital”, and “Keningau MP says he received MOH’s early release from Mandatory Quarantine”. A good government is one that reacts well under pressure, and COVID-19 being the defining factor, Sabah’s government has the exam right in front of them.

With only 12% of Malaysia’s population in the state, Sabah’s 19,898 active COVID-19 cases holds approximately 38% of the country’s overall cases. Sabah remains a priority to the federal government because poor roads to healthcare, accessibility to government services and unreliable electricity services make it all the more difficult to combat the pandemic – factors controlled by the individuals in power such as the state’s Members of Parliament.

From my personal experience in Sabah, the biggest thing I’ve learnt is that although ballots cannot be physically bought, money still talks. Money has bought the majority of 17,828 voters of N.40 Bingkor’s rakyat, because their struggle to get through each day is never guaranteed. And even though it has potentially led them to the same candidate who failed to improve the quality of their lives over the last two years he has served, it is the rough conditions and limited resources they have that forced that choice from them. Unfortunately for Bingkor’s rakyat, this desperate feature was used to Perikatan Nasional’s advantage for power.

Peter may have lost the hearts to the 60 kampungs of Bingkor, but to the DAP team who campaigned with him through the long hours, he’ll always be our champion.

Hayley Lee

*The views and opinions expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the DAP.