By Ivy Kwek

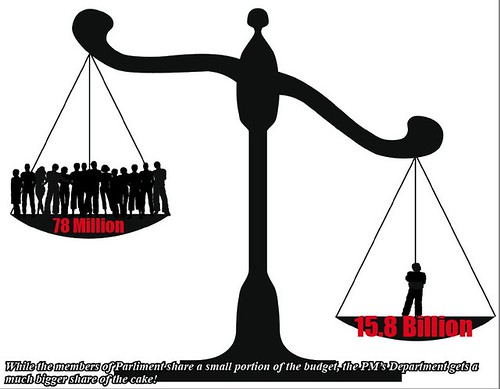

Standing at RM214 billion, the 2011 budget is the largest budget that Malaysians have received thus far. However, much of the hype has overshadowed an institution whose importance is often neglected – the Parliament. This year, the Parliament received an allocation of only RM78 million. Last year, RM66 million was allocated.

Standing at RM214 billion, the 2011 budget is the largest budget that Malaysians have received thus far. However, much of the hype has overshadowed an institution whose importance is often neglected – the Parliament. This year, the Parliament received an allocation of only RM78 million. Last year, RM66 million was allocated.

Though there has been increase in value, the amount Parliament received is actually insignificant compared to other agencies and ministries. The Prime Minister’s Department, the mega-ministry of Malaysia, received an operational budget of RM5 billion and a developmental budget of RM10.8 billion. A mere bureau in the Prime Minister’s department, Biro Tata Negara (BTN), is already costing RM66 million. Even the ministry that is smallest in budget size, Ministry of Federal Territories and Urban Well-Being, will be receiving RM584 million. In fact, the amount received by Parliament is actually only a 0.05% share of the total budget.

One should be reminded that the Parliament is made up of members that are elected by popular votes. Parliament, therefore, is the representation of people, at least in theory. It is meant to scrutinise the workings of the government, to legislate laws, to enable the government’s financial provisions and to address public grievances. Thus, it is ideally a channel to allow the public to have a say in the government policy.

Theoretically, the MP from the party or a coalition of parties that secures that confidence of the majority will be the prime minister and will form his or her own government. As Malaysia practices the parliamentary democracy system, it also means that the government will always be the majority in Parliament, as opposed to the presidential system in United States, where the president and the majority of Congress can come from a different party.

That would also mean that the policies proposed by the government will most likely be passed. But as ironic as it may sound, Parliament still has a role to play particularly in raising contentious issues. This has become apparent with more opposition MPs elected into the parliament in the last general elections.

Sadly, the lack of emphasis in empowering the democratic institution has longed handicapped the Malaysian Parliament from unleashing its full potential. Under the long domination of the governing party prior to the last general elections, the Parliament has turned into a mere rubber-stamp of the government.

Nonetheless, parliament should not be a centre stage for political drama, but the place where serious policy debates with substantial intellectual input that would lead to the better outcome for decision-making in the country.

Up to 2011, the budgets allocated to Parliament are all of operational nature – which is to say, the RM78 million is for the maintenance of Parliament and not for its expansion, whether through soft or hard infrastructure.

General Administration

RM22 million

House Management

RM51.7 million

Overseas Duties

RM3.4 million

Association of Parliamentary Librarians of Asia and Pacific (APLAP) KL 2011

RM200,000

Emolument for Contractual Staff

RM643,000

Considering that an MP gets monthly allowances of about RM 13,000 and that we have 222 of them, the amount alone will come near to RM35 million, almost half of the total budget already! Factoring in the paycheques of the 314 staffs in Parliament, there are virtually nothing left for value-added activity for the institution.

Much indeed can be done for Parliament in order to promote democracy.

First of all, more parliamentary committees should be formed to discuss specific bills or to investigate contentious issues in greater details, which is hardly possible in the formal House setting. An uncommon practice in Malaysia’s Parliament, this approach is widely used in other countries such as Australia and the UK. Such committees can help to facilitate the legislative process as it allows more meaningful bi-partisan discussions to happen. It also leverages on the expertise of different MPs by arranging them into committees according to their areas of concern.

These committees will then submit a report of recommendation to the House for consideration. In countries such as Philippines and New Zealand, the committees also actively engage the public by holding open hearings and forums. In South Africa, an institution called the People’s Assembly which meets once a year was established to bring people of all sectors together to reflect on the impact of the Bill of Rights and the Constitution on their lives.

In Malaysia, though it is provided for in the Standing Orders, committees are rarely set up to discuss bills except the Human Rights committee and the Public Accounts Committee (the other three committees are set up for internal administration issue).Here, after the second reading of the bill, the House will simply enter a ‘committee stage’ and pretend that they are a committee with 222 members. The only difference would be that the mace, which is lifted up to signify the house in meeting, will be lifted down during this period. As the result, most bills will only be able to secure a pathetic three to four-hour debate session.

Secondly, there are no provisions for individual research staff for MPs. In fact, other than the ministers, there are no individual office spaces provided for MPs, opposition and government backbenchers alike. According to the Senarai Perjawatan 2011 (list of jobs and positions), the research unit under the Parliament is staffed by 15 Grade 48 research officers, which leaves it clearly understaffed as there are 222 MPs that they are supposed to serve. In comparison, the Australian Parliament houses an extensive and well-established parliament research unit of 75 members including section directors, executive assistants, and researchers.

Workshops and awareness programmes organised by the Malaysian Parliament has been minimal, whether for the parliamentarians or for public. More efforts can be done in the capacity building for our MPs to empower them in their roles as policy-makers. Similarly, awareness programmes for the public should be conducted to help them understand the rationale of the institution and its relevancy to the nation’s well being. New Zealand, for example, publishes a handbook that advises the public how to make submissions to lobby the parliamentary committees on key issues.

Live broadcast of the House proceedings should be made available to the public, either via the web or television. Currently, only the first half hour of each day’s sitting is broadcast through national channel RTM 1. While the viewership is a separate matter, the move will show the government’s sincerity in promoting greater transparency and the acknowledgement that the people have the right to know the goings-on of Parliament. With the technology now available, this is a reform that can be easily accomplished.

These are a few proposed reforms that will not come at great financial expense of the country. If adopted, it will bring great impact to the policy-making process that will eventually benefit the people. Thus, it is up to the government of the day if they have the political will to make it a realit y.

y.