By Pauline Fan

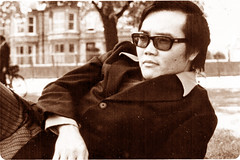

In Cambridge, 1973

Papa was a wellspring of strength and joy for the family; he was the deepest source of joy and laughter in my life. He loomed large in our lives; his presence was indelible, his charisma unmistakable. He was always a kind of hero figure for me and my sister. When we were young, we would watch him with awe working among his books, listen to him incessantly typing away on his old manual typewriter, and the scent of pipe tobacco that filled his study is still my favourite scent in the world.

“Farewell Papa...”

As I grew older, I began to understand that Papa’s work, his continuous engagement in politics and social issues, was inseparable from his life. He did not simply have a ‘job’; he lived out his uncompromising principles through his writings and actions, and was driven by his deep-seated ideals to fight for social justice and human dignity. For Papa, politics was the natural arena where citizens could exercise their rights and obligations in modern society. In the words of Papa’s literary hero George Orwell: “In our age there is no such thing as ‘keeping out of politics’. All issues are political issues . . .”

The complex layers of Papa’s personal history revealed themselves to me over time, like the hidden meanings in a poem familiar but not yet understood. When I was about nine years old, Papa took the family on holiday to Pahang, Terengganu and Kelantan to visit the various small towns where he had once been posted as a teacher in the 1960s – Kuala Lipis, Temerloh, Kota Bharu and Tanah Merah.

We travelled by train, his preferred mode of transport, and accompanied Papa as he traced the journey he had taken as a young teacher 20 years earlier. He deeply loved his country – its landscape, its people and their customs; and the East Coast remained specially cherished in his memory. We went to the seaside in Marang, then to the rather godforsaken town of Tanah Merah, adopted two kittens at the train station in Manik Urai, named them Manik and Urai and left them with his old friend Gopal in Kuala Lipis.

Only later did I discover that Papa had been posted to teach in these remote areas because of his active involvement in the National Union of Teachers (NUT). He had served as the NUT’s Director of the National Membership Campaign and Assistant Secretary of the Pahang branch and was the editor of ‘The Educator’, the official organ of the NUT. The authorities were particularly irked by his role as one of the co-organisers of the teachers’ strike of 1967, which helped bring about equal pay for women, as well as housing, pension and medical benefits for all teachers.

Similarly, I learnt about Papa’s political career gradually in the course of growing up, as one discovers another piece of a vast, living jigsaw puzzle – about his years with the Democratic Action Party (DAP) and how he served as Acting Secretary-General while Lim Kit Siang was detained under the Internal Security Act; about his terms as Member of Parliament for Kampar and Menglembu; about his sedition case for publishing a speech by Dr. Ooi Kee Saik in ‘The Rocket’; and about how he was disqualified from Parliament and deprived of his Member of Parliament’s pension.

While Papa was campaigning with the short-lived Social Democratic Party in 1986, I remember accompanying him to see his old printer who was preparing his campaign posters and leaflets. I remember too Papa’s disappointment when the SDP failed to win any seats, and how he then withdrew from formal politics and threw himself into writing and activism. Papa’s fighting spirit was irrepressible; even in his hours of political defeat and isolation, he remained convinced that political change was both necessary and possible.

Addressing the delegates at the 1st DAP Youth congress in 1973

Papa did not deliberately set out to ‘radicalise’ his daughters, but politics was such an elemental part of his being that we inadvertently imbibed his sense that Malaysia’s political landscape left much to be desired. One of the ways my sister and I spent time with Papa was to accompany him on his ‘wanderings’ to second-hand bookshops and coffee shops in Kuala Lumpur and Petaling Jaya, where he would run into friends and ‘comrades’ and engage them in vibrant exchanges of opinion about the latest political scandal or social injustice.

Papa was truly a man of the people; he could establish instant rapport with virtually everyone, from his loyal newspaper man, Balan, to Pak Ali, a devoted member of Parti Islam Se-Malaysia (PAS) who owned a restaurant in Taman Tun Dr. Ismail for many years. When my sister and I returned to Malaysia during our university holidays, Papa brought us along to several PAS and DAP ceramah as well as to various talks he was giving at Cenpeace or ABIM, where we witnessed the fiery oratory style that never left him. He also brought us to the Malaysian Sociological Research Institute to meet the intriguing chain-smoking activist and writer, Dr. Alijah Gordon, who was extremely fond of him.

Papa forged friendships that lasted for life. His relentless pursuit of social and political justice for ordinary people, as well as his vivacious personality and well-read intellect, endeared him to many the world over. Among his friends he counted Helen Clark, the former Prime Minister of New Zealand, and Malcolm Caldwell, the British Marxist scholar who was killed by the Khmer Rouge in 1978.

Papa believed in people and principles, not in systems and ideologies. I think this is why he was so fascinated by history, the narrative of humanity itself. Papa’s knowledge of history never failed to astound us. He could talk for hours on the history and politics of India (particularly the dramatic local politics of Tamil Nadu), or Willy’s Brandt’s Ostpolitik, or the fall of the Roman Empire.

And Papa believed in love. His romance with my mother was epic in every sense; turbulent at times, but adoring to the end. Shortly after my parents got married, my mother left for Cambridge to pursue her Doctorate. Undeterred by his aversion to air travel, Papa voyaged over land and sea, from Port Klang to Madras, across India by train, then by bus through Pakistan, over the Khyber Pass in Afghanistan, through Iran and Turkey and on to Europe, to join my mother in England in the winter of 1975-76.

Papa’s personal legacy to me is a passion he cultivated in me since childhood, a passion that shaped my life profoundly through young adulthood and continues to this day to mould who I am and how I relate to the world: an undying love of literature. Papa constantly invoked the spirit of the writers he loved most – George Orwell, James Joyce, and Albert Camus among others. He imbibed and lived, in his own flesh and blood, the writer’s life: he wrote only by hand or on his beloved typewriter, he smoked a pipe in the style of Bertrand Russell, he read voraciously, and his room was a labyrinth of books, newspapers, and magazines.

Papa was urged by an intellectual restlessness that is the mark of all true writers. He believed in the power of the written word to encapsulate the interminable drama of the human spirit, of the individual and society. Like the Russian writer Alexander Solzhenitsyn, Papa believed that “literature is the living memory of a people.” In fact, one of the last books Papa read from cover to cover was Michael Scammell’s acclaimed biography of Solzhenitsyn which Papa had picked up at a second-hand bookstore in Bangkok. Incidentally, Scammell had interviewed Papa about his sedition case in the 1970s for a write up for the ‘Index on Censorship’, the prominent British journal on political freedom which Scammell founded and edited.

Papa was urged by an intellectual restlessness that is the mark of all true writers. He believed in the power of the written word to encapsulate the interminable drama of the human spirit, of the individual and society. Like the Russian writer Alexander Solzhenitsyn, Papa believed that “literature is the living memory of a people.” In fact, one of the last books Papa read from cover to cover was Michael Scammell’s acclaimed biography of Solzhenitsyn which Papa had picked up at a second-hand bookstore in Bangkok. Incidentally, Scammell had interviewed Papa about his sedition case in the 1970s for a write up for the ‘Index on Censorship’, the prominent British journal on political freedom which Scammell founded and edited.

Language and politics were inextricably linked for Papa. His commitment to the written word reflected his conviction that writers had a duty to uphold the integrity of language, to employ it as a weapon of truth against a political rhetoric riddled with lies.

As Orwell remarked: “Political chaos is connected with the decay of language . . . one can probably bring about some improvement by starting at the verbal end”. It is this belief in the ability of language and literature to speak truth to power that urged Papa to read and write to the very end. I imagine Papa now taking his place among his literary heroes; I imagine him engaging in endless conversations (and arguments) with them, in a place beyond space and time, beyond history, beyond language – a place, in the words of the poet Yehuda Amichai, “where there is time for everything”.[THE ROCKET]