By Wan Hamidi Hamid

Forty five years ago, a unique debate about the idea of having a Malaysian cultural policy was held in Kuala Lumpur. It was unique because it was between two multiracial parties – DAP and Gerakan – debating about language and literature at the capital city’s MARA Auditorium.

Forty five years ago, a unique debate about the idea of having a Malaysian cultural policy was held in Kuala Lumpur. It was unique because it was between two multiracial parties – DAP and Gerakan – debating about language and literature at the capital city’s MARA Auditorium.

On 24 November 1968, the newly formed Gerakan led by its senior leader Dr Syed Naquib Alatas argued that Malaysian literature must be based on the Malay language, hence Indonesian literature must be included in the Malaysian culture. For Syed Naquib, literary works in other languages such as Chinese, Tamil and English, even if they were written by Malaysians, are not considered as Malaysian literature.

Kit Siang countered such a view, saying that if the policy was accepted, there would be no room for a Malaysian Chinese or Indian to express Malaysian nationalism, aspirations, struggles, hopes and sorrows, unless the person think and writes in Malay only. Since its inception in 1966, DAP has accepted the Malay language as the national language, as well as advocates multi-lingualism and cultural diversity.

Not many remembered this episode, compared to what happened six months later – 13 May 1969.

A memorable moment

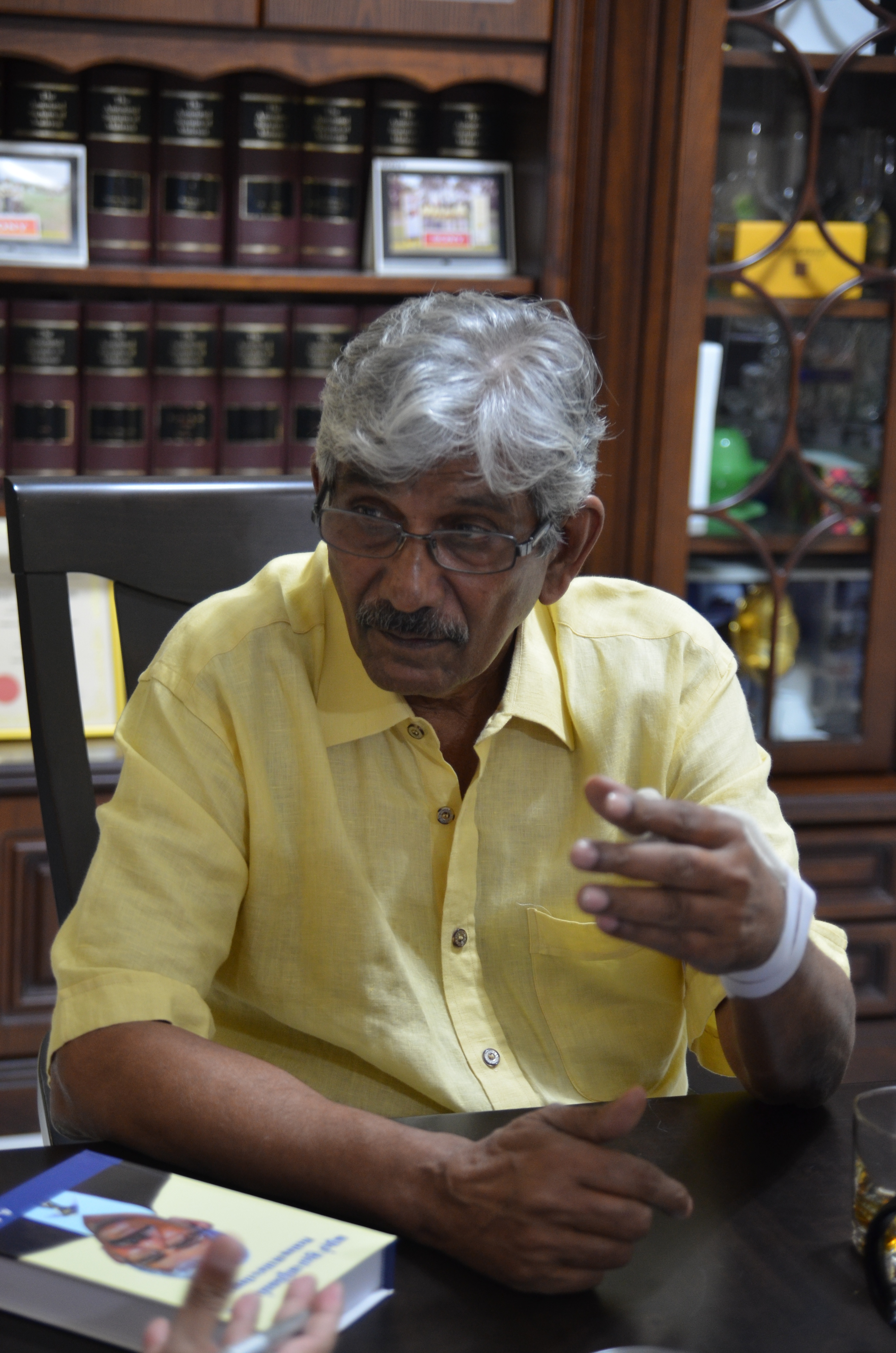

But for K. Siladass, who turned 75 this year, it was a historical moment. Kit Siang chose him, then a young leader from Johor who had joined DAP from the Labour Party a year earlier, to be part of the DAP debate team – the others were Goh Hock Guan, Fan Yew Teng and Ernest Devadason.

“Before the debate, Syed Naquib had been saying that Malaysian culture must be based on Nusantara culture while DAP said it must be based on multi-racialism. Even today, I believe in DAP’s multi-racial policy of having Malaysia as a melting pot. At the moment we’re only a salad bowl.

“For me, it’s a process. We look for something in common, with trial and error, and tolerance and perhaps we’ll achieve something good later on,” said the healthy-looking practising lawyer when met at his home in Kluang, Johor recently.

He remembered that although such a topic for the debate may be considered sensitive today, it was conducted in an open and fair manner. At least for him it proved that Malaysian society, although not perfect, was more tolerant back then.

In fact, when asked, he said UMNO leaders were smart enough not to get entangled in such a debate. “They were playing it safe. While there were UMNO Ultras such as Dr Mahathir Mohamad, they preferred to leave it to Syed Naquib to make noise over the issue of culture,” he added.

Siladass also believed that UMNO’s non-involvement in such a debate was due to Tunku Abdul Rahman’s leadership style of “leave us alone”, maintaining the status quo of race-based politics – i.e. leave the Chinese to do their businesses and the Malays to hold political power.

What is more important for Siladass is the fact that there was a debate, strong views were offered, ideas were exchanged and there were clash of ideas, yet no one was hurt, except perhaps for bruised egos. It was how a democracy should function.

But May 13 changed all that. No more such debates were held. People were scared. UMNO introduced power politics on top of the racial politics already in practice. The post-1969 era was a bleak moment for the country.

Life in Labour

However for Siladass, who was born in 1938, there are still many happy memories, no matter how tough the situation was for him. His own departure from his beloved Labour Party to DAP was one such bittersweet memory.

However for Siladass, who was born in 1938, there are still many happy memories, no matter how tough the situation was for him. His own departure from his beloved Labour Party to DAP was one such bittersweet memory.

The Labour Party was formed in 1952 by intellectuals and labour leaders of various ethnicities who modelled it after the British Labour Party. A decade later the party saw the influx of Chinese labour leaders, and many believed that with them, came along the idea of Mao Zedong’s communism.

But that was not a real problem. The Alliance government (predecessor to BN) had persecuted and oppressed the Socialist Front – a coalition between Labour Party and Parti Rakyat Malaya. This resulted in the left wing coalition losing a lot of seats in the 1964 general election.

This was the time of Konfrontasi when Indonesia’s Sukarno attempted to crush the formation of Malaysia, claiming it to be a Western neo-colonial plot. As some of the Parti Rakyat leaders were admirers of Sukarno, the Tunku government used it as an excuse to detain some of them under the ISA, including its leader Ahmad Boestaman.

In Singapore, PAP’s Lee Kuan Yew also used ISA to detain socialist leader Lim Chin Siong. This cruel act angered the Socialist Front leaders and members. Some of Labour leaders began to talk about extra-parliamentary actions. It gave the excuse for the police to infiltrate the party and caused trouble from within.

Siladass said that by the mid-1960s, he was the Segamat Labour Party secretary. He noticed that party membership began to increase with new members from the Chinese community. However he felt something was amiss when they began to have a different set of meetings.

“I thought it was just a passing fad for those young Chinese joining the party. But by the time the English-speaking members realised it, we had lost our ground. The hardliner Chinese-speaking members had taken over the party,” he said.

In Johor, he added that, Labour leaders’ decision to boycott the coming general election as well as to stage street demonstration as the party’s main political action made him realise that the Labour party was not going anywhere with such an attitude.

“By 1967, despite the strong rhetoric, all had fizzled out. Labour Party’s stand was too strong – either you boycott the election or you don’t do anything at all. By the late 1967, I left the party, because to me, there was no more party anymore. We had no activities whatsoever.

“I was in Kluang at that time. A former PAP leader Lee Kaw was there and he persuaded me to join the newly-formed DAP.

Life in DAP

However, it was not an easy thing to do. Siladass explained the curious history behind it all. “Not many Labour members joined DAP at that time. In fact it was like committing a sin if a Labour member joined DAP at that time,” he said.

Why? For one, Labour Party as part of the Malaya-Singapore socialist movement was against Lee Kuan Yew’s PAP whom they described as a right wing although PAP was formed by both the centrist and leftist politicians and labour leaders. Things became worse when Kuan Yew detained Chin Siong, the most popular socialist leader in Singapore, under the ISA. Hence, DAP being part of PAP’s legacy is seen as an “enemy” to the Labour Party.

According to Siladass, Labour Party members, including those who refused to help any opposition party in any elections after that, condemned him and any other ex-Labour members who joined DAP.

“To them, it was a conflict between socialists, between those who uphold socialism and those who abandoned socialism.”

So why did he join DAP?

“(Because Labour wanted to boycott the general election and) at that time, the only effective multiracial opposition party was DAP. So I accepted the offer to join the DAP,” said Siladass.

He began setting up DAP branches in Johor, in plantations and in new villages, assisting Kit Siang who was then the party’s organising secretary. He also campaigned for DAP for its by-election in Segamat Utara when DAP contested against UMNO’s Musa Hitam (who later became Dr Mahathir’s Deputy Prime Minister in 1980s).

DAP in the post-NEP era

After 1969, Tun Razak as Prime Minister managed to convince many opposition parties to join his new coalition Barisan Nasional. When Gerakan, People’s Progressive Party (PPP) and PAS, as well as some Sarawak’s opposition parties joined BN, the real opposition such as DAP was left in a lurch.

The formation of BN came after the implementation of the New Economic Policy. Despite its nice-sounding ideals, NEP was seen as a form of discrimination by the non-Malays. Siladass too saw the ideals of equality and equal opportunity eroded with the implementation of the NEP. Not that he is against affirmative action for poor Malays but he believes it must be based on needs, not on one’s race or faith.

As proven today, he said, the NEP has escalated into a form of UMNO’s special privileges, even the poor Malays who have no political cable with the establishment suffer at the hands of the rich UMNO cronies.

In 1973, Siladass changed his focus in life. He left politics to pursue his law degree in the UK.

Life’s reflections

“It was in the UK that I actually learned about political ideologies. During my younger days in Malaya and in Singapore, life was full of activism. Even if you had time to read, there were not many political writings or books you could read because the government had banned them.

“Come to think of it, our Chinese-speaking comrades in the Labour Party were luckier because they had access to some socialist literature in Chinese language,” he said, adding that he was more inspired to be a socialist after seeing images of Che Guevara and Castro in the newspapers. He said that even though the news were merely news, the government allowed photos of communist leaders to be printed as part of the world news.

Although he learnt more about socialism when he was in the UK, his focus was on law. He was and still is an expert in insurance and accident claims. He has written a number of books on those subjects and is now planning to write his memoirs.

In his younger days, Siladass studied in Segamat and later in Singapore. He also taught himself Tamil, enabling him to write both in English and Tamil. He is a Barrister-at-Law; Lincoln’s Inn and became advocate and solicitor at the High Court in the early 1980s.

He enjoys golf and was Vice President of the Kluang Country Club until he retired a couple of years ago. He is still a practising lawyer, and when he’s not in court, he spends his time writing.

Any regrets? “No, none at all. In fact I am so happy to see many young people of today coming out to participate in political activities. During my time, except for the young Chinese educated people, most English educated Malayans were reluctant to get involved in politics.

“Last time, there were virtually no media for the opposition. At least now you can create your own media through the internet. Last time we made circular notices by cyclostyle,” he added.

Reminiscing about his life, Siladass is convinced that he has done the right thing, both as political activist as well as a lawyer.

“It’s all about whether you are willing to take disappointment. Because the other easy way is to accuse or blame others. I never use politics as a springboard for anything except as a platform to do good things for the people,” he said, adding that he was once offered a seat to contest for DAP but had to decline for some technical reasons.

Despite the lack of infrastructures and amenities during the 1950s and 1960s, Siladass believes that those days were a slightly better era compared to now. “There were no snatch theft, no brutal murders, no kidnapping, and no gangsterism in politics.”

He said all the bad things now are bad for Malaysian culture. He reminds the current batch of leaders to think carefully. “You may have the best system but it will only work if you do the right thing.”

A Malaysian culture

So what is a Malaysian culture to Siladass?

He offers some simple anecdotes. Before Merdeka, he said, he knew of some Malays who would not hesitate to go a Chinese or Indian house for lunch or tea. And those Malays would not ask whether the food was halal or not because they knew their non-Muslim friends would understand their needs.

In another real life story, he related how a Malay senior fellow counsel recently asked him for tea. When he asked the Malay guy to go with him to a Chinese coffee shop, the person asked him “Is it safe?”

For Siladass, the powers-that-be have failed to create a Malaysian awareness that was supposed to enable Malaysians to understand each other, to respect one another, and to live together as human beings.

“Long before this new culture of “open house” we used to send food to our neighbours, be they Malay, Chinese or Indian. We exchanged food. That’s a beautiful culture. Are we still doing it now? Where is this culture?” He blames it on UMNO for bulldozing everything good about multiracialism.

Siladass is perplexed with the attitude of Malaysians. “When we were less prosperous last time, we were more tolerant. Now that we’re better off, we’ve become intolerant.”

All is not lost. The veteran lawyer politician believes there’s a bright future for Malaysia if Malaysians are willing to be Malaysians rather than segregated by race and religion.

“If we can replace the current practice of politics of convenience to politics of principles, I believe we can have a great future.”

For Siladass, he was and still is a socialist. Not a radical or revolutionary one but a democratic socialist, and he doesn’t mind being called a social democrat. For him, socialism means equality and equal opportunity, and nothing should be judged by one’s race or religion.

“Every human being deserved to be treated as human being. Now that’s social democracy. And from there you get social justice.”