The political crisis caused by the Sheraton coup should be seen as part and parcel of a very painful and long democratisation process.

The coup was in fact the form that the expected push back by conservative forces took, against the people’s democratic uprising that took place at the election box on 9th May 2018.

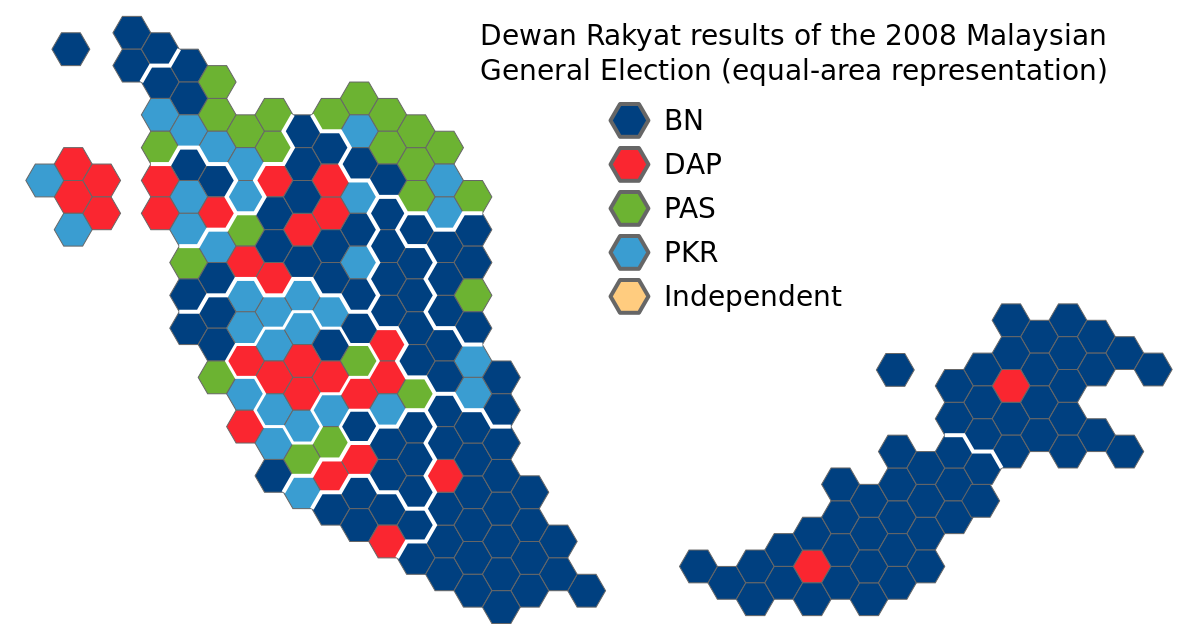

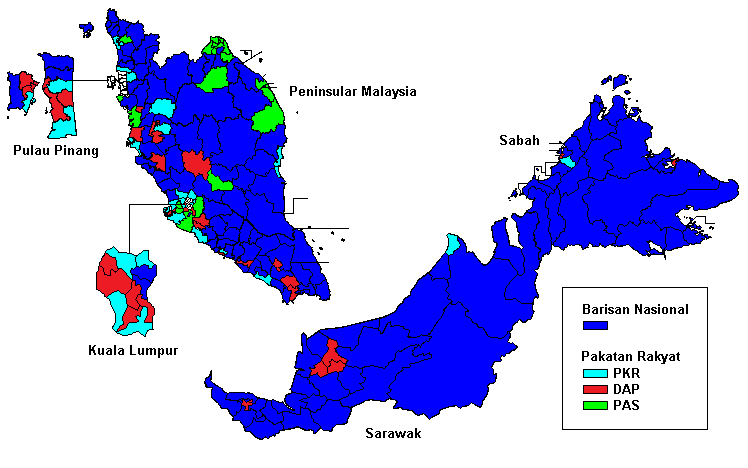

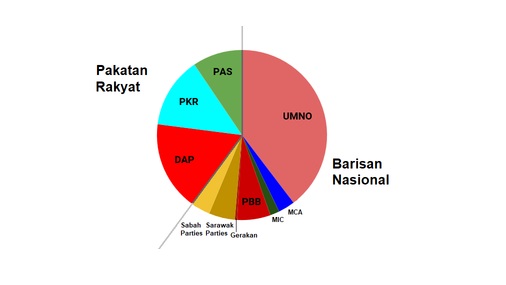

Malaysia had been a one-party state where people could not imagine change, and in fact fear it—up until the 2008 election that saw Barisan Nasional losing the two-thirds majority for the first time and falling in the most industrialised states, such as Selangor and Penang.

The 2018 general election witnessed Malaysians of all ethnic and religious backgrounds coming together in a huge turnout on election day to rise against the one-party state that attempted to win by:

- Setting a Wednesday polling day (to reduce turnout)

- Changing election boundaries (to favour the ruling coalition)

- Attempting to use the Election Commission to ban even the photo of Tun Dr. Mahathir Mohamad; not to mention interventions in the mass media etc.

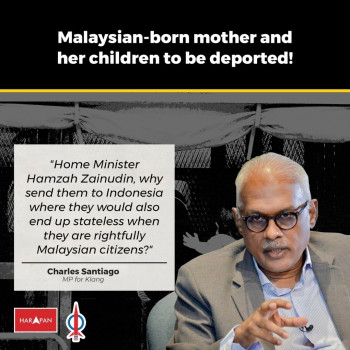

Upon losing, the conservatives regrouped and attacked the Pakatan government on ethnic fronts:

- Claiming to the Malays that the government had been hijacked by DAP and the non-Malays.

- At the same time, suggesting to the non-Malays that Dr. Mahathir controlled everything to the detriment of the non-Malays.

The “scorched earth” strategy worked. Trust and support for the Pakatan government collapsed within a short span of time.

To bring together the grand coalition of Dr. Mahathir and Datuk Seri Anwar Ibrahim in 2017 was extremely difficult. But to hold it together after winning power in 2018 proved to be even harder.

Trojan horses had penetrated the defences. Tan Sri Muhyiddin Yassin on Mahathir’s side and Datuk Seri Azmin Ali on Anwar’s side pulled the rug from under these two leaders.

The government fell as a result.

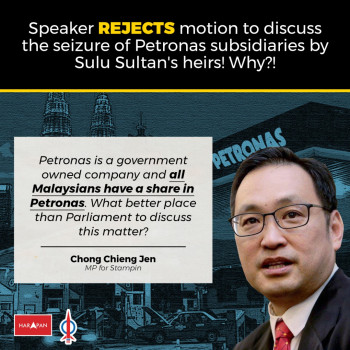

But the result of these shenanigans, is the new government, the Muhyiddin-Perikatan Nasional government, is the weakest in Malaysian history. It is not confident enough to try to prove that it has a majority in parliament; and at the same time, UMNO and PAS are waiting to pounce on Muhyiddin’s and Azmin’s separate factions.

On the opposition bench, at the same time, the cleavage between Mahathir and Anwar makes reclaiming of the ruling mandate very difficult. Talk of a looming general election is getting louder as well.

Here are five points that should help us understand the current political situation.

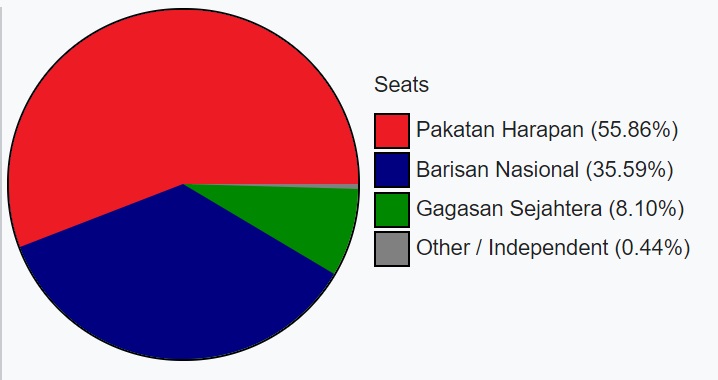

1. A 50-50 electorate

In the 2008 general election, Pakatan allies received 47% of the popular vote.

In 2013, support for them went up to 51%.

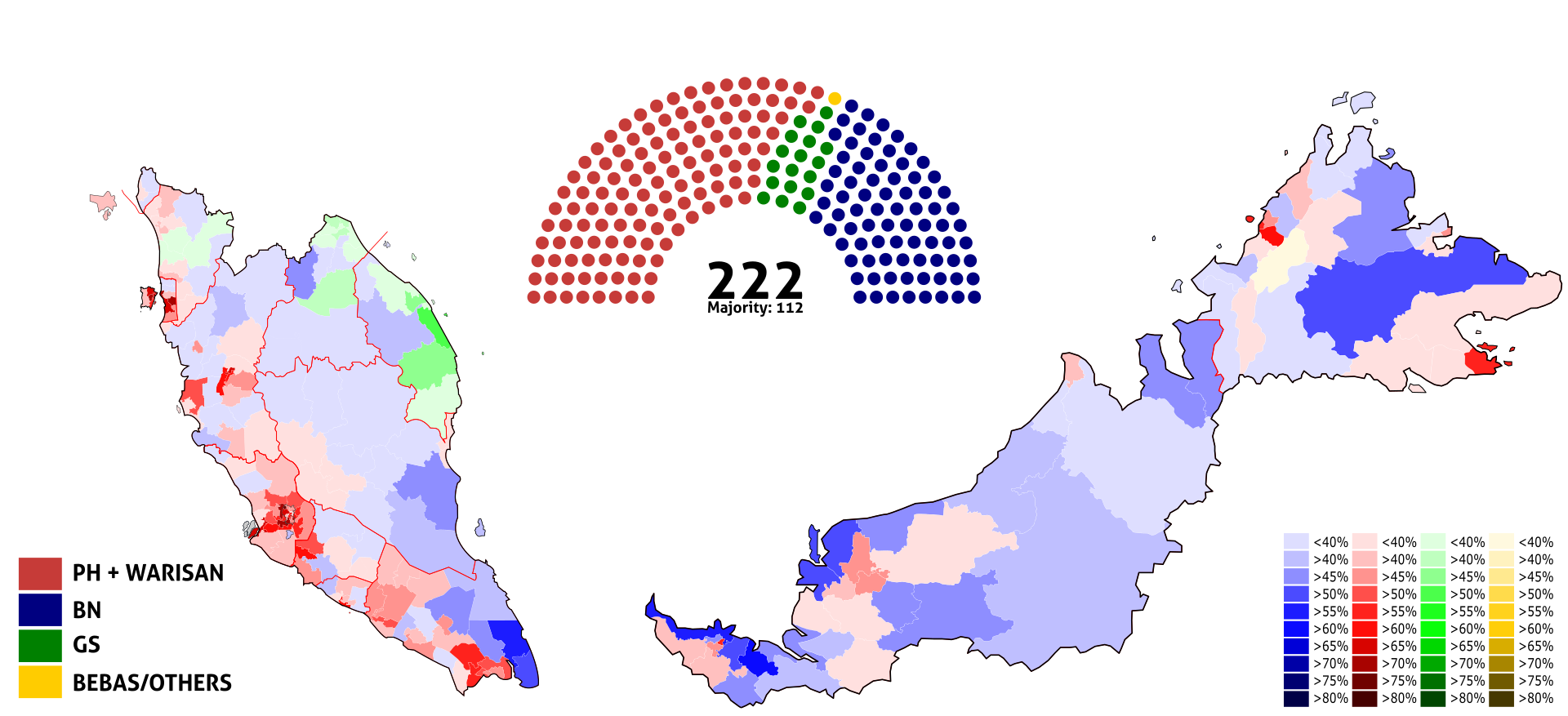

In 2018, they gained 48% of votes in a three-cornered situation.

The widest gap we can expect in the next election is likely to be 55-45.

Such is the nature of democracy in most countries. The divide runs down the middle, more or less. There can therefore be no social peace when any Malaysian government acts as if it is running a country with 90 percent of popular support.

Governing parties have to learn to create democratic space for the opposition so that when it becomes the opposition, it will enjoy that space as well.

Opposition parties should learn not to burn the house down using racial sentiments as it just renders the nation ungovernable. This comes back to bite you—and this is what Perikatan Nasional has had to face.

2. Coalition realities

Coalition politics is likely to be the norm.

It is highly unlikely that any party can win more than 70 seats in a Malaysian parliament with 222 seats.

Gone were the days when UMNO alone, by winning more than 100 seats and being the dominant hegemon in its coalition, could control the country.

Governments in the foreseeable future will likely be coalition governments of relatively similar strength.

Every party will have to learn how to accommodate its coalition partners to achieve greatest common good.

Moving forward, institutions and governing styles should hopefully reflect these multi-party coalition realities so that every coalition partner can feel that their interests and constituencies are represented without having to have its leader as Prime Minister.

3. The “East Wind”

Of the Peninsula’s 165 seats, Pakatan won:

- 80 seats in 2008

- 80 seats again in 2013

- 98 seats in 2018.

Based on this alone, it is wishful thinking on the part of some members in Perikatan to claim that they can win a two-thirds majority in the next elections.

I acknowledge that Pakatan may lose some seats on the peninsula, but I am confident that Pakatan will hold the line at 80 to 85 seats.

80 to 85 seats in the peninsula may not bring Pakatan back to government. But if there is a swing in Sabah and Sarawak for Datuk Seri Shafie Apdal and his allies, it is possible that they can win 30-35 seats out of the 57 seats in Sabah, Sarawak and Labuan.

With this “East Wind”, taking over power from Perikatan at the federal level is a possibility.

4. The last hurrah for one-race champions?

Perikatan Nasional came into power with the idea that a one-race government is a superior idea. I maintain that such an idea is only good for a coup but never good in an election.

I told Muhyiddin during my final chat with him before the Sheraton coup that Bersatu being on the same side with UMNO and PAS will make it even harder for the three parties to carve up seats to contest in a general election.

The one-race champion, upon holding office, will have a hard time explaining the economic and other struggles faced by ordinary Malays for want of having an “Other” to blame. At the very least, they cannot put any blame on the DAP.

The anger against “dua darjat” (two classes) becomes more apparent when the privileged Malays linked to UMNO or Perikatan received special treatment during the MCO while ordinary Malays languished in jail. The one-race champion will also face the anger and scrutiny on the presence in its coalition of corrupt leaders, from middle-ground Malay voters who wish to see their country run by a clean government.

Pushing for a one-race ticket will also alienate non-Malay voters and Sabah/Sarawak voters.

5. Democratic uprising

The 2018 election was a democratic uprising pulling together all forces who were against Najib Razak and Barisan’s rule.

We must explain to Malaysians that if all forces attempting to establish clean government and democracy do not come together, they are paving the way for Perikatan to perpetuate its undemocratic rule.

If snap polls is called, all forces opposing Muhyiddin and Najib should therefore come together to fight them.

Civil society organisations and all Malaysians who want to preserve and strengthen democracy should acknowledge that we are faced with very strong conservative and regressive forces; and the only way to push back is to work together in a grand coalition to win at least 130 seats on election night to form a stable majority.

Only by understanding these realities and acting strategically, can we start afresh to mobilise our collective efforts in reclaiming Malaysia’s democracy.

Let it be clear that we can only achieve this feat if we stand together.

[Note: This is the first part of the abridged introduction of Liew Chin Tong’s book, “The Great Reset”. Read the second part here. The e-version of the book will be available on 12 July 2020 and the printed version on 25 July 2020]