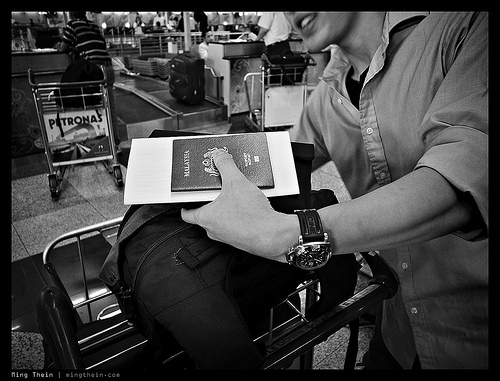

A taboo topic for many government policy makers, the brain drain issue has been capturing the Malaysian media headlines for unsavoury reasons. Not least since the report published by the World Bank titled “Malaysia Economic Monitor: Brain Drain” (MEMBD) that came out at the beginning of the year has scathingly laid down the facts about Malaysia’s worsening brain drain situation. However, the brain drain is only a symptom of the underlying economic malaise that is plaguing the country.

One million Malaysians living in exile

According to the World Bank report, it is conservatively estimated there are around 1 million Malaysians living overseas with about a third of them highly educated and skilled professionals, i.e, brain drain. It also estimated that around 10 percent of the country’s skilled and educated workers have left for other countries.

According to the World Bank report, it is conservatively estimated there are around 1 million Malaysians living overseas with about a third of them highly educated and skilled professionals, i.e, brain drain. It also estimated that around 10 percent of the country’s skilled and educated workers have left for other countries.

The report also states that the top three reasons cited by the brain drain emigrants for leaving Malaysia were diminishing career prospects (66 percent), grievances toward government and public policies (60 percent) and low compensation levels (50 percent).

Tellingly, an overwhelming number of the Malaysian emigrants are Chinese, which represented 88 percent of the total diaspora population.

Singapore appears to have been the prime beneficiary of this exodus, registering 57 percent and 54 percent of the diaspora and brain drain from Malaysia. If daily commuters to and non-resident Malaysian-born workers working in Singapore are counted, around 20 percent of Malaysia’s skilled and educated ones are contributing to other countries’ economic well-being.

NEP driving anguished Malaysians away?

Malaysia, while not the only country afflicted by the brain drain issue, suffers because of self-inflicted blows in the form of self-defeating economic policies and stagnating economic growth resulting from corruption and governance inefficiencies.

The New Economic Policy (NEP) which started off as means by the government to address the economic inequalities then inherent in Malaysia in the 1960s, has grown to encompass many spheres. Many economic sectors saw bumiputera-preferential encumbrances being placed, with the supposed aim of allowing the bumiputeras to catch up. .

Yet for the intended beneficiaries, the majority of the bumiputeras have not seen their income levels grow in tandem with the other races. In fact, the wealth disparity in intra-ethnic terms has worsened. According to another World Bank report titled “Malaysia Economic Monitor: Inclusive Growth” published in November 2010, the Gini coefficient of wealth equality measure for the bumiputera community stands at around 0.44, not far from Malaysia’s 0.45 figure which is one of the highest in Asia.

According to researcher Jayanath Appadurai’s estimation of Malaysia’s poverty rates, who used a more realistic threshold of monthly income level of RM 2000 compared with the government’s absurd RM 800 per month for households to measure poverty levels, 73 percent of Bumiputera households are earning below the poverty level. (Centre for Policy Initiatives, 28 July 2010).

Furthermore, in 2010 the government has admitted that of the RM 54 billion worth of shares allotted to the Malay community since the 1970s, only RM 2 billion remains in Malay ownership. Has the NEP failed?

Education inequality is another cause of resentment for many non-bumiputeras. The public uproar over the Public Service department’s inept handling of tertiary education scholarships and university placements for Malaysia’s best students, which mostly affects the non-bumiputera students, seems to have become an embarrassing annual event for the government. It breeds resentment for these school leavers from an early age.

The non-bumiputera perception of the government’s lop-sided treatment favouring of bumiputera students, rightly or wrongly, is a difficult mindset to change once formed at this impressionable age. The sense of non-belonging began to set in for these Malaysians; a flight to greener pastures is not a difficult decision for them.

Malaysia bleeds as corruption flourishes

It is an open secret for the public that the corruption level in the country is endemic. Transparency International (TI) has estimated that Malaysia loses RM 10 billion or more than one percent of its GDP annually to corruption and its deteriorating TI Corruption index rankings of 23 in 1995 to 56 in 2010 attests to that assertion.

As a result, Malaysia has been losing out on attracting foreign direct investments (FDI) in the last few years to its South-east Asian neighbours, including the Philippines in 2009. Malaysia is now facing the middle income trap of not being able to push forward with value-added and knowledge-intensive industrial growth due to its dwindling skilled and educated workforce base and lack of private investments.

Another irony is Malaysia’s lax policy of admitting low-skilled and educated foreign migrant workers. From around 500,000 in 1994, Malaysia now has over 2 million legally documented migrant workers with another several million undocumented ones. Yet in the corresponding period, the foreign expatriate population has dropped from around 80,000 in 2000 to below half that figure in 2007 (New Economic Model report, 2010).

Is Malaysia contented to let its brightest leave while helping other countries shoulder their poverty burden by providing jobs for their poor?

Failed mitigation costing Malaysia billions

Under Dato Seri Najib Razak’s watch, there have been more determined efforts put in place to address this slide. Beginning with the New Economic Model (NEM), Economic Transformation Programme (ETP) and Government Transformation Programme (GTP), there is now an open acknowledgement for the need to tackle the economic malaise. However, progress for these efforts has been anaemic.

One of the prominent steps mooted and taken up is establishing the Talent Corporation to attract back Malaysian expatriates to the country (refer next story).

Piecemeal effort by the government in the past has yielded muted gains for the country; it was reported that the Returning Scientist programme implemented since Tun Dr Mahathir’s tenure had gained only 23 returning scientists while Tun Abdullah Badawi’s Brain Gain programme attracted less than 3,000 applicants during his administration (The Malaysian Insider, 14 July 2010).

The MEMBD report has estimated that Malaysia has potentially lost out on USD 11.5 billion of FDIs in the period from 2007 to 2009, which is more than three times what it received for the same period, due to its self-defeating economic policies and innovation shortcomings (i.e. brain drain). Will the current efforts work? -The Rocket