By Charles Santiago

Malaysians will celebrate the country’s 56 years of being a sovereign nation, in the next two weeks, with the theme being: My Sovereign Malaysia: My Native Land.

Malaysians will celebrate the country’s 56 years of being a sovereign nation, in the next two weeks, with the theme being: My Sovereign Malaysia: My Native Land.

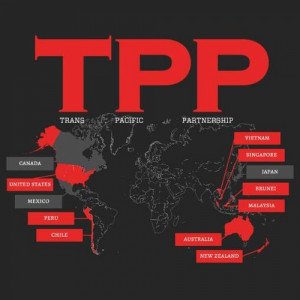

Plans to commemorate the day with pomp and bursts of color are already underway. But when the speckle of glitter settles, the theme will come to a naught. And this is because Malaysia would sign on to the Trans-Pacific Partnership Agreement or TPP. A highly controversial aspect of the TPP is the Investor-State Dispute Settlement (ISDS) mechanism listed in the Investment chapter.

The ISDS mechanism has serious ramifications for sovereignty and policy making space of governments. Or more importantly, ISDS allows corporations to discipline governments and its institutions. It gives power to corporations to sue governments in international arbitration tribunals such as the World Bank’s International Center for Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID) or the Paris based International Chamber of Commerce (ICC).

The decisions of these tribunals are final and binding on governments. And awards of the tribunal can be enforced anywhere in the world, including taking possession of government property elsewhere.

Recently, corporations have chosen the ISDS strategy in resolving conflicts with governments. Since 2011 there were 450 known investor state cases, the majority of which were filed by corporations against developing nations. The context of the ISDS system has changed. What started as a fair and neutral dispute settlement system has now mutated into something else.

A research by Transnational Institute (TNI) has shown that arbitrators tend to defend private investor rights above public interest, and that the ISDS system is now “a multimillion-dollar, self-serving industry, dominated by a narrow exclusive elite of law firms and lawyers whose interconnectedness and multiple financial interests raise serious concerns about their commitment to deliver fair and independent judgments.”

Other recent studies on investment treatise and arbitration also show that the process falls short of basic standards of transparency, judicial independence and procedural fairness. To further strengthen the interests of corporation, the ISDS mechanism does not stipulate investor obligations but only investor rights.

This further cements corporate control over sovereign nations.And most importantly, in signing on investment treaties and agreeing to arbitration, a government willfully accepts to be sued in a jurisdiction outside its own legal framework.

For example, the US-based tobacco giant, Philip Morris, is suing Uruguay and Australia over health warnings on cigarette packets.

Swedish energy multinational Vattenfall is seeking $3.7bn from Germany following a decision to phase out nuclear energy in the country after Fukushima.

US-company Lone Pine is suing the government of Canada for US$250 million over a moratorium on controversial shale gas extraction (fracking) in Quebec.

Philippine government spent US$58 million defending two cases against German airport operator Fraport. These are funds that could have paid the salaries of 12,500 teachers for one year or vaccinated 3.8 million children against diseases such as TB, diphtheria, tetanus and polio.

Hence, here is the crucial question: What is at stake for sovereign governments?

They can be compelled to pay millions or billions in damages for loss in profits. Authority and policy making space of governments, sanctity of laws enacted by parliament, and jurisdiction of the national courts can be undermined.

The case of Philip Morris against the Australian government succinctly proves my argument.

In 2011, the Australian government introduced new regulations on cigarettes packaging in an effort to reduce smoking-related health problems. Tobacco giant Philip Morris reacted by filing a lawsuit in the country against the government as it perceived the decision of the government was detrimental to its investments, causing loss in profits.

In 2012, the country’s High Court ruled that the regulation was justified and tobacco companies did not deserve compensations as it is a public health measure. Philip Morris has now referred the case to ICSID seeking billions of dollars in compensation through the ISDS mechanism under the Australia-Hong Kong Bilateral Investment Treaty.

This could happen to Malaysia if it decides to sign-on to the Transpacific Partnership Agreement.

The Ministry of International Trade and Industry (MITI) has brushed off concerns regarding ISDS. They argue that the ISDS is needed to attract foreign investment and that Malaysia is already subject to the system resulting from various trade agreements, even without signing the TPP.

The government should not fall prey to corporate lobby. Investments and FDI are a function of a stable government, good infrastructure, an educated working class and a system that guarantees transparency, good governance and zero corruption.

Malaysia must also beef up its own investment laws to protect both local and foreign businesses to ensure fair and equitable treatment and not succumb to the ISDS oversight.

In the last few years, countries such as Bolivia, Ecuador and Venezuela have terminated investment treaties and withdrawn from ICSID. Argentina has refused to pay arbitration awards. South Africa has said it will not renew old investment treaties which are about to expire. And lastly, Australia has announced it will no longer include ISDS provisions in trade agreements.

Malaysia should follow these examples so that we can continue celebrating our independence as a sovereign country.

_____________________________________________________________________________________________

Photo credits to malaysia-chronicle.com

_____________________________________________________________________________________________

Pingback: TPP: Corporate Rule over Sovereignty and Public Interest | PR