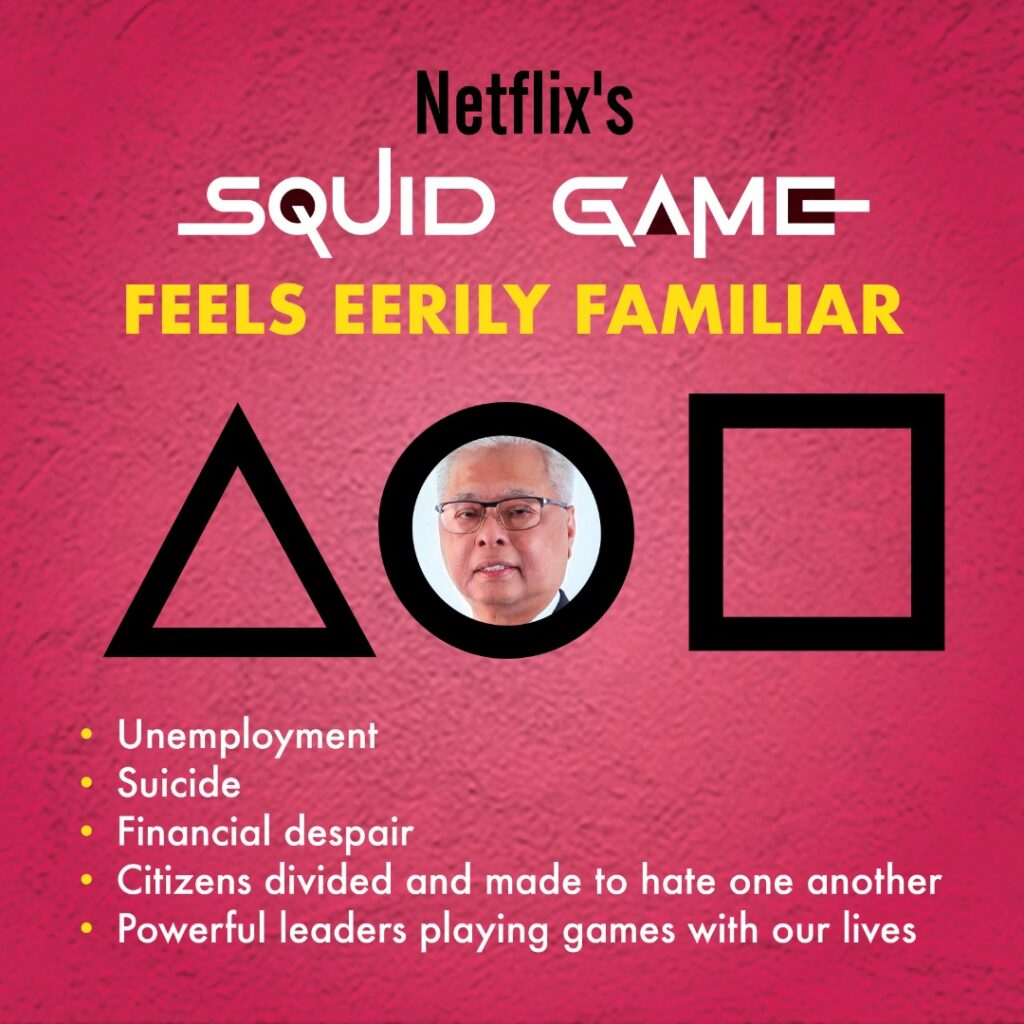

The premise of Netflix’s wildly popular show, Squid Game, is simple enough: 456 players compete in a series of Korean childhood games to win 45.6 billion won (roughly RM160.4 million). Lose a game, instant death. Why would anyone play?

1. The illusion of choice in late capitalism

The players have nothing to lose. They are all economically desperate. Seong Gi-Hun (player 456) is a kind-hearted deadbeat dad and gambler who steals his mother’s ATM card to bet on horses. There’s a North Korean deserter who wants to smuggle her family, a securities trader wanted for embezzlement, and a Pakistani undocumented worker cheated of his salary.

Amidst this setting is class inequality. Despite tremendous economic prosperity since 1961 (dubbed the “Miracle on the Han River”), South Korea’s youth unemployment rate peaked at 27.2% in January 2021[1]. Suicide is especially common among senior citizens living on the edge of poverty, like Gi-Hun’s mother who is forced to work despite her advanced age and illness. South Korea’s economy is dominated by chaebols – conglomerates owned by a few powerful families, such as Samsung (Lee family) and Hyundai (Chung family). Chaebols are interlocked with government interests, sparking “too big to fail” concerns during the 1997 Asian financial crisis. They also are accused of monopolistic practices due to protectionist policies.

Malaysia too faces a similar conundrum, albeit in the form of government corporations. In his book Minister Of Finance Incorporated, Prof. Dr Terence Gomez highlights the immense influence of Government-Linked Investment Corporations (GLICs) and Government-Linked Companies (GLCs) through ownership of media companies and conglomerates[2].

Meanwhile, as of May 2021, Malaysia’s youth unemployment rate was about 12.7%[3]. Pre-Covid-19, it was already three times higher than the adult rate[4].

Now, are the realities of life truly worse than the situations faced by Squid Game players? Stunned by the bloodiness, Episode 2 depicts players immediately voting to end the game and return to their lives. Yet reality is unbearable, driving many to return to the deadly games. This is the illusion of choice in late capitalism. While Squid Game takes this to extremes, we must ask: what terrible conditions do we tolerate for a better life? The exploitation of foreign worker Ali (199) reminds us of the xenophobic comments during the Pasar Besar Selayang cluster, the Home Ministry’s negative reaction to Al-Jazeera’s report on migrant worker sufferings[5], and photos of foreign workers rounded up and sprayed with sanitizer. How is our reality different from fiction?

2. “If you’re poor, you’re lazy”

Playing fair is supposedly paramount in Squid Game. However, in Episode 7, a glassmaker (player 017) can differentiate glass tiles based on light refraction. To appease VVIPs watching the games, the lead organiser (“Front Man”) switches off the lights, rendering 017’s skills useless. Similarly, we often hear the upper class preaching about fairness. But, the way they act betrays “dua darjat” tendencies as they have no qualms in purposely changing rules to gain an edge against the less fortunate.

Take the Pandora Papers. Over 11.9 million leaked confidential files showed global power players (including politicians and public officials) benefitting massively from offshore tax havens. While having overseas assets, companies or trusts isn’t illegal, they can be abused for tax evasion or criminal purposes. 1MDB springs to mind. Meanwhile, citizens are expected to pay taxes regularly.

Wage disparity is also an issue. Recently, deputy human resources minister Datuk Awang Hashim told Parliament that in the Malaysianization programme under Penjana 3.0, the government would loosen the minimum wage requirement from RM1,500 to RM1,200 to encourage employers to replace foreign workers with locals. This supposed “solution” clearly shows the deputy minister’s lack of understanding of realities on the ground. The minimum wage still needs raising, not further reduction, especially in cities where costs continue to rise. The fact that there are thousands of Malaysians working in Singapore’s service sector shows that locals are willing to work in difficult and dangerous jobs provided the pay is right.

3. Weakening of labour movements and class solidarity

Throughout the show, game organisers actively pit players against each other. After being deprived of food, players engage in a kill-all at night, when cooperation would’ve helped them beat the rules. Similarly, capitalism and racist politicians pit workers of different races against each other to prevent class solidarity.

We also see in Episode 5, that Gi-Hun was involved in a workers’ strike which was brutally repressed by the police. Malaysia’s trade union movement has seen a steady decrease in unionised workers. Judgments favouring workers have not sparked major legislative change. Hospital cleaners in Perak are still fighting for their promised increment, restoration of their previous public holidays and medical allowance benefits, and the issues raised by the #HartalDoktorKontrak movement are pending.

Can Malaysians break out of the Squid Game?

(Major spoilers ahead) Despite the trauma he underwent, Gi-Hun’s character remains almost the same as he was before playing the Squid Game. He’s still rash and a deadbeat dad. However, he is not without some redeeming qualities – one of which is not succumbing to the rules and compromising his humanity in the final game. The series ends on a cliff-hanger: will Gi-Hun try to take down the organisers of the Squid Game?

It’s easy to oversimplify Squid Game as humanity being doomed because we’re inherently greedy. The reality is that people do desperate things because of desperate situations, which is exploited by the system for profit and even entertainment.

As we grapple with the impact of various scandals on our country’s finances and the mismanagement of Covid-19, will we come out the same? Or will we have the willpower to change towards a kinder, more equitable society?

Lim Yi Wei

State Assemblywoman for Kampung Tunku