By Pauline Wong

Way back in 2002, there was a relatively short-lived American sitcom called ‘8 Simple Rules.’ The sitcom was based on a book titled ‘8 Simple Rules for Dating My Teenage Daughter’ , in which a father lays down eight rules for any boy wishing to date his teenage daughter.

The premise of the sitcom is simple: it revolves around the Hennessy family, whose overprotective father John struggles to do his best to protect his daughter Bridget from, well, boys in general.

By now you are probably confused as to where this article is going. No, it is not about the tudung-clad girls hugged by the girls — I mean, the boys of a K-Pop band.

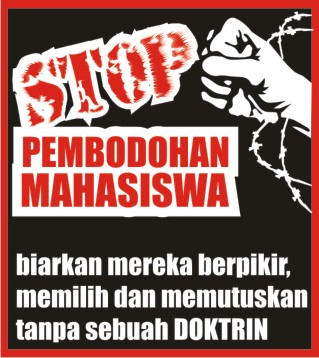

It is about the mollycoddling and cocooning of our undergraduates, who like teenage girls, are poised to ‘go forth into the world and into adulthood’ when they graduate.

In this case (see where I am going?) the overprotective ‘father’ is the government, but unlike a father simply trying to protect his daughter from harm, the government is doing our undergraduates more harm by wrapping them in a bubble of ignorance until they are 65.

And, unlike the rather funny sitcom of the early-2000’s, there is nothing to laugh about the ongoing clamp-down on student and academic freedom.

This is dead serious.

Students cocooned away from the “big bad world”

One could say that the cocooning of our undergraduates began with the Universities and University Colleges Act 1971, which forbids student participation in politics or political parties. Some believe that the Act was created to end student influence on the political sphere, especially in the aftermath of the deadly 13 May, 1969 race riots.

The “student power” movement as compelling as in the 60’s was never seen again after that, and the UUCA became a spectre, looming over student’s heads.

Then on 25 April 2010, during the Hulu Selangor by-election, four Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia (UKM) political science students were held by the police on their way to Kuala Kubu Baru. They had been carrying PKR campaign materials in their cars, because a party member had offered to show them around.

Subsequently, UKM officials appeared and said that the UKM four would be subject to disciplinary action for breaching the Universities and University Colleges Act (UUCA). After a bitter two-year battle, they finally won: The Court of Appeal declared in 2012 that Section 15 (5) of UUCA was indeed unconstitutional and students can openly express their support, or opposition, of any political party.

The UUCA was also amended to allow political participation, but the victory seemed short-lived.

Even after the UUCA was amended, it appeared that the universities began taking it upon themselves to impose the same restrictions.

In October 2013, Malaysian students on Public Service Department scholarships in Australia were forbidden from attending a talk by opposition leader, Datuk Seri Anwar Ibrahim, on the threat that they would lose their scholarships if they did.

In December 2004, Malaysian students at Indonesia’s Universitas Gadjah Mada (UGM) were forbidden by the Malaysian Embassy in Indonesia to attend his ceramah too.

And in a circular issued early-2012 by the Kolej Universiti Islam Antarabangsa Selangor (KUIS), all students were forbidden to attend or participate in ‘illegal demonstrations and street protests’, or ‘the college would not hesitate to take action’ against students who defy the order.

Then, last April, DAP Selangor chief Tony Pua was dropped as a speaker in a Malaysian student event in Australia after sponsors decided that his not-attending would be ‘in the best interests of everyone’.

Last October, disciplinary action was taken against seven University Malaya (UM) students who had organised a talk with opposition leader Datuk Seri Anwar Ibrahim — a talk which the university forbade.

Universiti Malaya authorities have banned political involvement for its staff. Pic credit: James Brown (Creative Commons)

Students are not the only ones getting the brunt of the overbearing ‘protection’ of their universities; academic staff are also being pressured by the powers-that-be.

Last June, UM Centre for Democracy and Elections (UMcedel) head Professor Dr Mohamad Redzuan Othman, was pressured to leave and his contract was not renewed on ‘orders from the Education Ministry’, who —rumour had it — was unhappy over several polls which the pollster published that was unfavourable to the BN government.

UM law professor Azmi Shahrom was also hauled up under the Sedition Act for one of his articles on the Perak crisis. Azmi was later ‘chased’ out by security guards at Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia (UKM) after he was invited to lecture on the dangers of the Sedition Act.

Just last week, UM authorities issued a circular to all academic staff that all political involvement would incur disciplinary action.

And, in the latest blow, activist Marina Mahathir revealed on her Facebook that she was ‘banned’ by university officials from entering the university for a talk.

This list is hardly exhaustive, but it already paints a grim picture.

Stifling student’s thoughts leads to… unemployable graduates

How can the country expect critical-thinking graduates and create valuable human capital if the education system stifles any sort of critical discourse? If indeed one were trying to develop well-rounded individuals, capable of determining right and wrong, how is one to do that by feeding students a diet of one-sided propaganda?

To speak plainly, cling-wrapping students to ‘protect’ them stunts their intellectual growth, and lends to graduates who cannot rise to the challenge of today’s world.

Already we have seen the evidence of this ‘protection’:- according to the Higher Education Ministry in 2012, out of a total 184,581 graduates, 44,391 people or 24 per cent are unemployed. Two years ago, English daily The Star ran a story where employers said that the education system is not producing ‘thinking graduates’.

The paper quoted Manpower Staffing Services country manager Sam Haggag as saying that there was a distinct gap between what the Malaysian education system is producing and what employers are looking for, as the universities are churning out graduates who don’t have the requisite skills to enter the workforce.

Aside from a lack of English proficiency, they also lack the communication skills that employers need. Haggag said one reason for the lack of confidence evident in young graduates is that educational institutions are not placing enough focus on equipping undergraduates with skills that will enable them to think out of the box and adapt to the demands of the working world.

In that report, Hong Leong Bank chief human resources officer Ramon Chelvarajasingam also said many of the new graduates lack the critical thinking skills required to keep up in a world that is constantly changing and becoming increasingly competitive.

So who are the government really protecting? But more importantly, who will save our undergraduates? -The Rocket