By Pauline Wong

Someone is always watching: A cartoon illustration from the International Herald Tribune demonstrates this.

Have you ever got the feeling you were being watched? Chances are, you are. By the government.

More than a year ago, public relations executive Justine Sacco tweeted that “Going to Africa. Hope I don’t get AIDS! Just kidding. I’m white!”

The head of PR for a New York-based internet company, Sacco tweeted that remark just before she boarded a plane for a 12-hour flight.

In that 12 hours, social media went to town — the tweet was shared, re-shared, re-tweeted and soundly condemned for its insensitivity and racial stereotyping. Perhaps Sacco meant it to be a satirical and provocative tweet on the disease that kills millions in the poorest nations in Africa, one would never know.

But whatever her intentions were, by the time she landed, her life was effectively destroyed. She was fired from her job and now lives in the shame of having been caught being a racist on the internet.

Closer to home, entrepreneur Siti Fairrah Ashykin Kamaruddin, or better known as Kiki, was filmed bullying and aggressively shouting at a 68-year-old man who had bumped into her brand-new car at an intersection in Kuantan last July.

She even took his steering lock and proceeded to hit his car with it, shouting abuse at him while she did so.

The video, uploaded to Facebook last July by one of the passers-by during the incident, went viral within hours, and her Facebook account and personal details were laid bare for all to see, and to shame. She was even the subject of several memes, many of which showcased the steering lock.

She was charged in court, found guilty, and fined for the assault — something which would probably not have happened if the video was never uploaded on social media. Probably.

Unfortunately, that is how social media works. The world, the government, your mom, that weird friend you have not seen in years but added on Facebook— they are all watching.

Yes, we’ve all had that feeling of being watched, but never has it been so true as with the advent of social media. No matter where you are, or what you think is ‘privacy’, someone is watching and can destroy your life in seconds, like Sacco and Kiki.

Anything you click ‘send’ into the great big internet can come back and haunt you.

Or, in the case of Lawyers for Liberty co-founder Eric Paulsen, lead you to being arrested by 20 burly policemen.

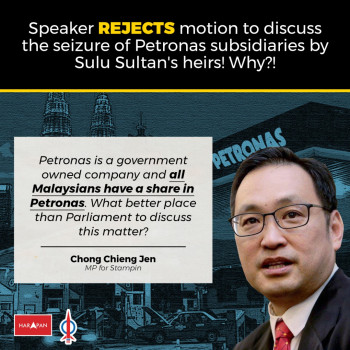

Paulsen, who has 2,200 followers on his Twitter account, had last Friday reportedly tweeted “Jakim is promoting extremism every Friday. Government needs to address that if serious about extremism in Malaysia.”

He later clarified that it is a criticism towards the Islamic Development Department, and not towards Islam itself — but that did not stop Deputy Prime Minister Muhyiddin Yassin from demanding ‘swift’ action against Paulsen for the tweet.

And swift it was – the police picked Paulsen up that same night.

Sedition Blitz of 2014… and 2015?

Paulsen’s arrest under the archaic Sedition Act 1948 was the first Sedition arrest of 2015.

He now joins the ranks of the 20 people, including academician Azmi Shahrom, who were arrested, detained or questioned by the police under this pre-Independence Act last year. Even MalaysiaKini journalist Susan Loone was not spared what was called the ‘Sedition dragnet” of 2014.

The Malaysian Communications and Multimedia Commission also made some arrests of their own, one of them being Twitter user Effi Nazrel Saharudin who tweets under the handle @1Obefiend. Effi was charged for insulting the Agong.

Then, in a total reversal of his previous stance, Prime Minister Najib Abdul Razak reneged on his promise to repeal the Sedition Act, which explains why this colonial era law is still a shadow looming over our heads.

Just last week it was revealed that Universiti Malaya had sent a circular banning its staff from participating in any political event and ordering them to “uphold the dignity and reputation” of the country and government at all times.

While there is no excuse for being offensive on social media, the fact is that freedom of expression is a fundamental human right.

Any attempt to stifle this right — such as the Sedition Act, whose broad brush is vague and all-encompassing — is against the spirit of the Federal Constitution which guarantees this right.

So for a government that claims itself as a ‘transformative’ and ‘forward-thinking’, the clamping down of these civil freedoms is at odds with its claims. It surely does not help the government in the global arena, nor in its aim to be a developed nation.

Why does it continue to do so, then?

A government that has not changed with the times

Perhaps the answer is that the government has not yet come to understand the way information is shared has changed, and is now beyond their control.

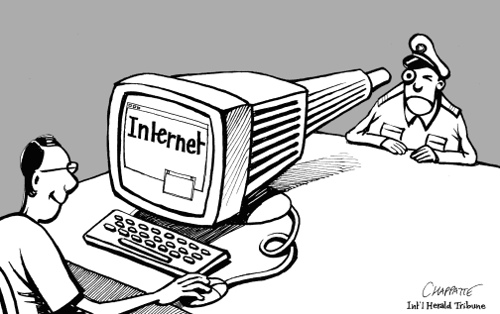

Lawyer Syahredzan Johan in his column in The Star yesterday observed that before the Internet came to be, information was monopolised by the state, where information flow is controlled and dictated by the state.

“When the Internet happened, this monopoly slowly eroded…the biggest development was the emergence of social media; with it, everyone can share content,” he wrote.

This, he said, has greatly impacted the socio-political landscape. Now, politics and governance must not only be done but be seen to be done on social media.

“The democratisation of information created an empowering effect on the people. It was as if people suddenly realised that they had a voice, they had rights and they could exercise it. Freedom of speech and expression flourished on the Internet and even more so on social media,” he said.

But while social media has done much good, it has also done much harm.

“The challenge when it comes to social media can be distilled as such – the need to balance freedom of speech and expression with limits to those freedoms. Where do we draw the line in the sand when it comes to freedom of speech and expression?” he said.

In this, he said that the state’s response in dealing with these challenges appear disproportionate to the mischief it may be trying to address.

“The response to the challenges posed by social media seems to be the closing of the democratic public spaces through state action… (but) our approach to these challenges must be tilted towards the upholding freedom of speech and expression, and for the law to only step in the extreme circumstances,” he said.

This is where, it appears to the casual observer, the government has failed; by shutting down the doors of open discourse, it does itself no favours because the people will not stand for it.

It is imperative that the government comes to this understanding: that information is beyond their control, and they must change with the times. -The Rocket