By Pauline Wong

In 1960’s America, a writer named Jane Jacobs went toe-to-toe against one of Manhattan’s richest men, and won.

The battle was over the construction of a massive highway, the Lower Manhattan Expressway (Lomex), which would cut through her little village of Greenwich and displace thousands from their homes and businesses.

Jacobs, who did not have a college degree nor any formal training, was a vociferous critic of the overwhelmingly-male city planners as they sought to build more highways and roads post-Depression.

Often called a “crazy dame” or disparagingly referred to as ‘that housewife’, Jacobs was openly opposed to the Lomex and the man who conceived it, Robert Moses.

Her goal was one of social capital, a sort of ‘eyes-on-the-street’ concept where cities were organic, dense, and had a sense of community. People knew each other, and the city was people-focused, not automobile-focused.

A concrete monstrosity like the Lomex, she felt, had no place in this city she wanted.

Moses was a polarising figure at the time, being responsible as he was over the urban planning of the entire city. Jacobs, a mother and activist, had ‘no business’ taking on a man like Moses, much less winning one over him.

However, Jacobs eventually organised a huge opposition movement against the highway, and in the early 60’s the project was scrapped.

Here in Malaysia and some 50 years later, the same problem which worried Jacobs is now the burden of the hundreds of Petaling Jaya residents who may be about to live under the (literal) shadow of the Kinrara-Damansara Expressway (Kidex).

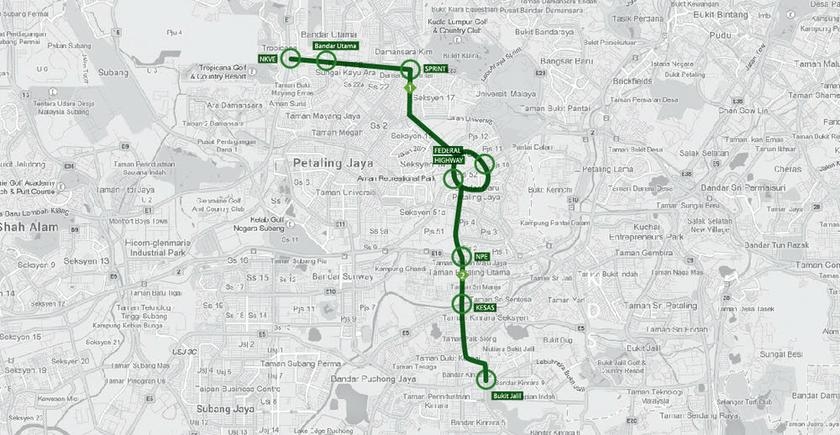

A15-km long highway which would stretch across Puchong, Petaling Jaya and Damansara, the Kidex was proposed last year and was immediately met with fierce opposition from residents, led by the Say No To Kidex (SNTK). The project has been rejected by the PJ city council after an independent review, but as the final say belongs to the National Highway Authority, it is uncertain if that will put an end to Kidex.

The arguments against the project has been heard numerous times.

First, the highway is no guarantee that traffic would improve in the very densely occupied areas which it is supposed to serve. The people behind the project have yet to provide concrete proof that it will, and if the excuse is: “No highway in the world can guarantee that” then why build it at all?

Second, the pollution this project would cause is no small matter, and in some stretches, the distance between the highway and some homes is less than 5 metres. In fact, the route cuts right through large residential areas and is a hair’s breadth away from a primary school.

Third, the project has been kept as if it were a great secret, with very little information available to the public at first. Although more information has become available since, the question of ‘who said yes first’ remains unanswered.

Fourth, road sustainability experts have long stressed that building more roads do not equal less traffic, but more. Former Malaysian Institute of Road Safety Research (Miros) director general Prof. Dr Ahmad Farhan Sadullah previously told the The Heat newsweekly that urban highways like Kidex are often an after-thought.

“As such, the alignment will be chosen to fit the congestion relief requirement, and as such the alignment will weave around build up areas. When this happens, road hierarchy will be flouted and therefore, the areas along the urban highway will receive the congestion spill-off,” he was quoted as saying.

He also added that as existing highways become more congested, more highways will be proposed and the vicious cycle never ends.

A less-often heard argument

However, the argument that is less often heard is how it would destroy the hope of a people-focused, pedestrian-friendly city, making cities like Petaling Jaya a ‘sprawl’ where people drove everywhere — from one cold, grey, concrete building and onto a dull, grey, tarred road.

Jacobs would have been appalled to not only hear of Kidex, but of the five other highways the government has planned for the Klang Valley, turning Malaysia’s capital city of Kuala Lumpur into one giant maze of highways and roads.

Come year 2020, Klang Valley would appear a tangle of grey snakes from above, strangling all the square dots of houses in its grasp, because the five other highways in the works are:

>> The RM1.18 billion Duta-Ulu Kelang Expressway (DUKE) extension;

>> The RM 5.04 billion West Coast Expressway (WCE) from Banting to Taiping;

>> The RM4.18 billion Damansara-Shah Alam Expressway (DASH);

>> The RM4.3 billion Sungai Besi-Ulu Kelang elevated highway (SUKE);

One more which has gotten Cabinet approval but have not been signed with any contractor is the Serdang Kinrara Putrajaya Expressway (SKIP), according to the Works Ministry. There is also an East Klang Valley Expressway (EKVE) but there is no word on whether that has been confirmed yet.

Is that the city we want, truly?

It is all to easy to cry out that opponents of the Kidex as ‘anti-development’, but that would be the most short-sighted thing to say.

What the critics of these highways are saying is they are anti-overdevelopment.

Even as city planners across the globe are beginning to realise that urban highways and automobile-centric transportation are no longer viable nor sustainable, the Malaysian government chooses to build more highways.

In the acclaimed documentary ‘Urbanized’, the Mayor of Bogota, Colombia Enrique Penalosa says that many things about city planning is counter-intuitive.

“It seems to us that building bigger roads or elevated highways will solve traffic jams, but that has never been the case. What creates traffic isn’t the number of cars on the road, but the length and number of trips. The more road infrastructure you build, then, will make traffic worse. The only way to solve traffic jams is to restrict car use, and the best way to restrict car use is to restrict parking. People imagine that parking is a fundamental human right, when it is not,” he says.

Public transportation, he adds, is true democracy in action — why should more road space be given to one person in one car than 100 people in a bus?

Bogota, where the car population went up from 950,000 to 1.5million in the late 2000’s, needed an alternative.

Penalosa, who was mayor from 1998 to 2001, put in place the world’s first large-scale Bus Rapid Transport system (BRT) and a 400km network of cycle lanes, backed up with pro-cycling policies including car-free days and closing certain streets to cars on Sundays.

As a result, bicycle use increased from less than 0.5% to 2% in just three years, traffic was reduced up to 40% and the bus system, the TransMilenio, was estimated to be three times more efficient than the New York bus.

As a city whose air pollution is so bad that a report in 2010 ranked respiratory disease as the number one killer of Bogota’s children, efforts had ground to a halt after a succession of different mayors put bicycle lanes and public transport on the back-burner.

Today, Bogota is one of the most congested cities in the world, with an average commute time of 72 minutes.

The concept of a city focused on moving people without over-dependence on private vehicles is a sound one, marred over the years by man’s long-standing love affair for cars and more cars. As economic reasons come to play — more wealth, a growing and profitable automobile industry — the need to think ahead is set aside.

A typical Malaysian household has two cars, or even more; driving is the only way to get anywhere since there are no bicycle lanes to speak of, and public transportation is simply not efficient enough.

Although new rails are being built, the connecting infrastructure of dedicated bus lanes or even punctual buses leave much to be desired.

We would be Bogota in a decade, if not less, if there isn’t a realisation that buying more cars and building more roads is simply unsustainable.

So what would it take?

It would take more than one Jane Jacobs among us to push for a city we want to live in — a city that does not have enormous elevated highways flying over our heads, obscuring our view of the night sky.

We need to push hard for public transportation, for ways to commute without using private cars carrying just one person. We need to understand that driving and cars is a privilege, not a right.

Sure, we may be able to drive to Puchong much faster if the Kidex is built — but how long do you think that will last? In a few years, even the Kidex will be as congested as say, the Lebuhraya Damansara Puchong (LDP). Would we build more highways then? When will the vicious cycle end?

And, when you run out of space to build highways, what then? If the government — state or federal — cannot with conviction answer those questions, then they have no business building highways across our skies.

-The Rocket